Superpowers #3: Nanyak Biyala (spirit of redgum tree)

words by Belinda Briggs

artwork by Kasia Fabijańska

The Print Council of Australia’s Superpowers project, funded by Creative Victoria, is a writing and printmaking endeavour. This is the third of the four specially commissioned essays and art work in which writers and artists interrogate various forms of energy in the context of the global climate emergency. Words: Belinda Briggs Artwork: Kasia Fabijańska.

13 November, 2020

In Exhibitions,

Printmaking, Q&A

Artwork:

Australian Inc.

In the urgency to string a sentence that will convey succinct articulations of multifaceted and interconnected relationships between my Yenbena (Ancestors) and Woka (Country) I am met with a rush of thoughts, memories, emotional or spiritual attachments that emerge from deep and far reaching places. Firstly, a trickle and quickly a torrent, before rising and rushing as if to fill voids of my innermost self where I truly begin at my roots, parched of nourishing teachings that span time, generations, and paradigms. [1]

On Biami’s Woka straddling the sacred Dungala (Murray River) are the Yorta Yorta heartlands. Floodplain country, famous for the largest living stand of river redgums in the world; taking in wetlands, the Barmah and Moira lakes, and gentle undulating sandhills, they are all part of one and the same story. Their existence is a tell-tale sign in the land, where on Biami’s instructions Dunatpan (rainbow serpent) was sent to keep watch over the old woman as she journeyed down from the mountain, making her way to the sea.

As she walked, her digging stick drew a line in the sand, of which Dunatpan followed. His body carved the earth into what became the riverbed, then filled with rain from a thunderstorm cast by Biami and giving life to our Dungala.

The old woman, weary from her long journey, went to sleep in a cave, and Dunatpan returned to the spirit world of Nanyak. Surging through Woka and pulsating through countless generations to all my grandparents, my parents to me, flows our Nanyak (creation or dreaming).

I share in it with others of Yorta Yorta. To share in it is to be attuned to each other, the cyclical cues of seasons with the emergence of new life or the departing of another; cold and hot, wet and dry; streams running, rivers breaking and spilling over their banks; water replenishing Country, then receding, to leave behind a chain of ponds and lagoons; the appearance of mist atop the river water, cloud formations, thunder storms; gentle breeze, blustery and icy or roaring hot winds of the south, east,

north or west; celestial forms in the nights sky, the rising and setting of the sun and moon across our skies. This is my Ancestors’ Country; my grandparents’ and parents’ Country; my Country, my sons, nieces, nephews, already their children’s and grandchildren’s Country.

My Ancestors lived it in the sites they made home, the water or foods that they gathered and which nourished them, the fibres they wove and crafted; the bark that transported or sheltered them, the wood they carved that they then wielded to maim, shield, discipline or hunt with; the plants that healed them; the ochre, feathers or bone that adorn their bodies; the trading of goods and the ceremonies danced and sung.

To those who call these lands home, they are most commonly referred to as ‘redgum’ or by the colloquial term ‘widow-maker’, owing to the dropping of its huge branches at times when under stress from the elements.

Western science would have you believe their name is eucalyptus camaldulensis. All throughout river countries and in places where water seeps, trickles, pools, or flows, it goes by different names. In Kaurna, it’s Karra, Wiradjuri Biyal or Mutti Mutti Piyali; in my Woka Yorta Yorta, along the Kaiela (Goulburn River) and Dungala (Murray River) and its tributaries, its name is Biyala.

Biyala and Dungala work in co-operation; the seasonal floodwaters stimulate growth and carry new seeds to take root; in return Biyala supports the cleansing of waters and the replenishment of nutrients for the fish, plant and animal life.

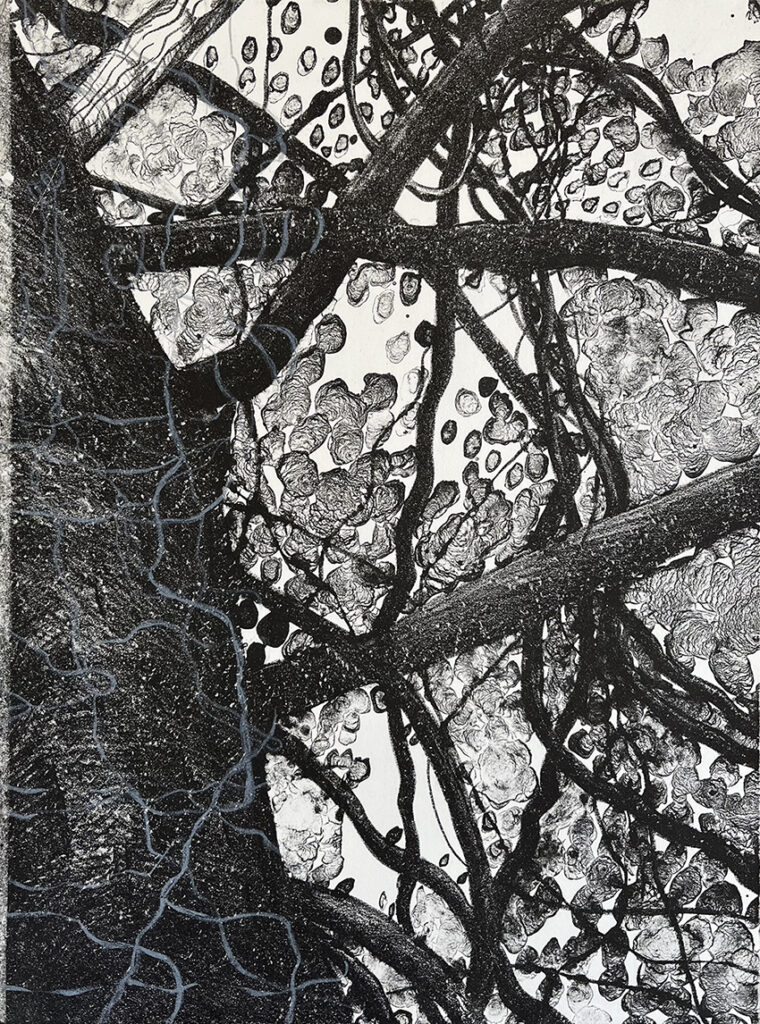

Our picturesque Biyala, of age old antiquity, have been a frequent subject of beauty and wonder for many Australian artists, including our very own world-renowned Yorta Yorta artist Lin Onus. They appear to stand like dancers in frozen formation for a garradha (dance), each with their own role to play across the land and along the riverbanks. Their smooth but sometimes gnarly trunks burst up from the earth, their branches stretching, bending, or curling as they can, fanning out as they reach for the sunlight.

The only movements visible to the naked eye are the leaves and branches in the wind or a bird at the entrance of a hollow for those trees of age. They are our keepers, healers, provider of tools, weapons, sustenance, watercraft, vessels for nursing infants, or holding food; a place to take refuge, birth our babies or a means for navigating Woka.

They make good fires to cook our food, shape our tools or keep us warm shielding us from the cold. They are expressions of our Nanyak, from where all spirit resides, as are we; part of and embodying the complex network of interrelations between the earth, ourselves and the spirt realm that is Nanyak and makes us Yorta Yorta.

Sentinels of time, they line the river banks, standing guard and watching over as families cool down in the summer with a swim or while we sit quietly, fishing line in hand. Life has long left some, apart from those creatures that now make it home. Others feature the scar from where a canoe or shield was carved from its bark. Their presence are affirmations of our belonging over many generations.

Up close, standing in the presence of the oldest Biyala, stirs the same feeling before my watchful Elders: admiration, awe and deep respect. At their base, some roots are so large and pronounced they beckon you to take a seat and rest. They are lifelines, travelling out and along Woka before diving down into the depths below in search of Wala (water). Their crowns, a wide expanse of large branches and infinite slender leaves, serve to protect you from the harsh light of the sun.

‘Grandmother’ or ‘grandfather’ trees, as they are sometimes referred to, is a way to denote their wisdom and locate them in family, standing as survivors like us. They embody a life lived, resilient and wise to overcome the odds.

Bearers and witnesses to the violence, the displacement of its caretakers, the disappearing of its families, the ceasing of dancing and singing its stories. These have been replaced with foreign bodies, beliefs, inventions and practices that exist in perpetual conflict with Woka over six generations, bringing an ongoing tension between humans, natural order and indeed Yorta Yorta people.

British invasion and ensuing ‘first’ explorers, colonial settlers, convicts and squatters, short-circuited, disrupted or appropriated this symbiosis of relationships for their own purposes and needs. Ancient relationships that are a means for this energy to flow, that breathe life into red gums and Woka, were being severed. With the first explorers traversing our Woka in the 1830s, it was a mere four decades later when the first concerns about unsustainable timber harvest practices were expressed.

Logging has cast a long shadow to the present day over the health of Woka, so too the clearing of land, waterways becoming highways for the moving of goods, water regulation and introduction of sheep and cattle grazing in the 1840s, which saw the beginnings of this lasting assault to the present day.

Simultaneously, at the time of these events, Yorta Yorta faced a grim future and little option for continuing or resuming the prosperous, autonomous, and equitable lives they once enjoyed. It was the early 1870s when they were first placed on Maloga Mission. Having already endured four decades of apocalyptic change, the devasting impacts to Yorta Yorta people and the disruption to their practices that uphold those relationships has a direct correlation with the decline in health of the natural values so many are striving to protect now. Despite the violence inflicted, the disease we suffered, mistreatment and this new life imposed upon us, our Ancestors’ Nanyak was still resolute and they were seeking recognition for interference of their rights as early as 1861, when it was made known to a representative of the Aboriginal Protection Board who reported:

Since the Murray has been navigated by steamers, the natives have found it scarcely possible to catch fish, heretofore their chief means of support. A native of the Moira (Yorta Yorta), who rode up the Murray with me, informed me of the intention of himself and five other Aborigines to proceed as a deputation to His Excellency the Governor to request him to impose a tax of £10 on each steamer passing up and down the Murray, to be expended in supplying food to the natives in lue [sic] of that which had been driven away. [2]

Some twenty years later a petition was put to the Governor at the time by forty-two residents of the Maloga Mission, requesting a ‘sufficient area of land to cultivate and raise stock; that we may form homes for our families [and in] a few years support ourselves by our own industry’. They asked this as compensation, ‘because all the land within our tribal boundaries has been taken possession of by the Government and white settlers’. [3]

Over the course of this short timeline, there have been some twenty documented assertions and claims to our Woka in the form of letters, petitions or claims through the courts. These sovereign acts do not include the micro and macro-violence averted and resisted by individuals, families and whole clans up until the present day. For the love of their families and Country, fathers, mothers and Elders have borne the brunt of the white man’s gun, his greed and inhumane policies and treatment. For all those confrontations documented, many more remain undocumented. The evidence, though, lies in the absence, silence and voids we urgently seek to explore, understand and fill. Our survival, resilience and determination are evident but it is our values and connectedness to Nanyak that holds us true. As newborns we arrive in the world with a pre-existing relationship to the world we will inherit through our mothers. Through her motions and those early sounds in utero, our instincts are primed in readiness to ensure our basic needs to survive are met.

Formed in the womb and familiarised to the rhythms of life and people in it, our bodies, mind, spirit, and heart are receptacles for information ready to be translated into physical, mental, emotional responses. Before our mouths have even mastered the gymnastics of words, the strength and coordination to control our limbs we are already in constant communication with the world around us, and it with us. Through all our senses, including that sixth sense, we have a constant flow of information sparking, charging, and flowing through our being.

I don’t remember ever not feeling a sense of connectedness to both the Dungala and the Barmah forest and surrounding country it flows through. This vessel, my body, bones, the blood in my veins and spirit, does not forget.

Maybe Aunty Hyllus Maris (1934-89, born on Cummeragunja, nee Briggs) said it best when describing who we are. She wrote:

I am a child of the Dreamtime People

Part of this land, like the gnarled gumtree

I am the river, softly singing

Chanting our songs on my way to the sea

My spirit is the dustdevils

Mirages, that dance on the plain

I’m the snow, the wind and the falling rain

I’m part of the rocks and the red desert earth

Red as the blood that flows in my veins

I am eagle, crow and snake that glides

Through the rainforest that clings to the mountainside.

I awakened here when the earth was new

There was emu, wombat, kangaroo

No other man of a different hue

I am this land

And this land is me

I am Australia.

–Hyllus Maris [4]

—

Notes

1. My love and gratitude to those who extended advice,

support and wisdom in composing these words. I

stand in solidarity with Djabwurrung Country, their

Ancestors, Elders and families for the loss of their

‘grandfather’ tree.

2. (Victorian Aborigines Protection Board, Annual

Report, 1861:19).

3. (Barwick, 1972:47; Cato, 1976, Appendix. 10). Two years

later, this resulted in the present day Cummeragunja.

4. ‘Spiritual Song of the Aborigine’ by Hyllus Maris in

Gilbert, Kevin (ed), Inside Black Australia: an anthology

of Aboriginal poetry (Penguin: Melbourne), 1998, p60.

—

Join the PCA and become a member. You’ll get the fine-art quarterly print magazine Imprint, free promotion of your exhibitions, discounts on art materials and a range of other exclusive benefits.