From top:

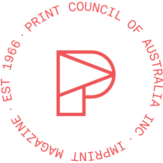

Zoe Haynes-Smith, Tree Medicine ll, 2022, folded digital print, 60 x 60 cm

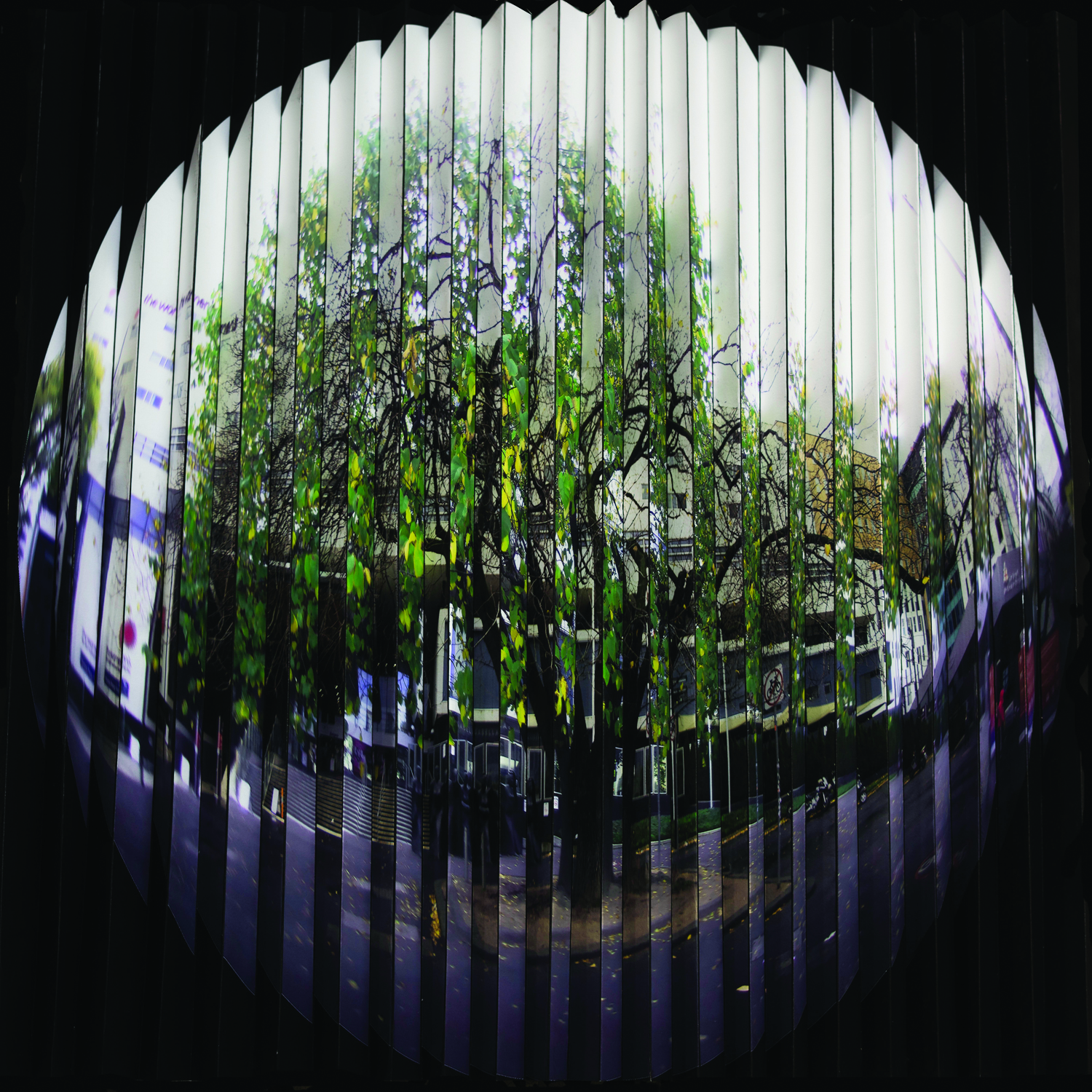

Erica Elgin, Outside observation I, II and III, 2022, Copper plate aquatint on 300gsm paper 356 x 762 mm

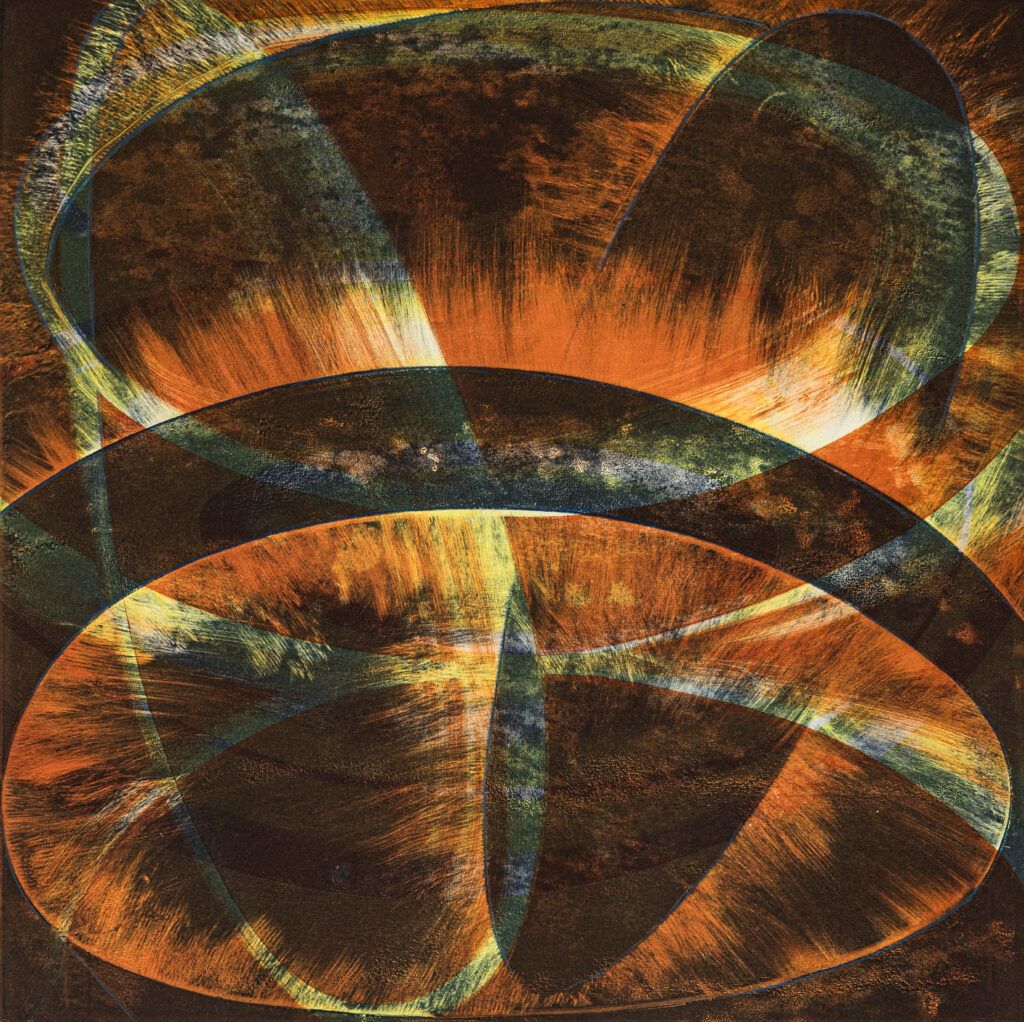

Heather Hesterman, Gingko I, 2022, screenprint with ink made from gingko leaves on BFK Arches paper, 3/3 (additionally, there are 5 Unique States available), 38.5 x 28.2 cm

Bridget Hillebrand, Traces, 2022, linocut and chalk on kozo paper, 120 x 65 x 5 cm

Kathy Holowko and Sarah Moore, Drawing Tree, 2022, 100% recycled cotton paper and markers, 30 x 30 cm

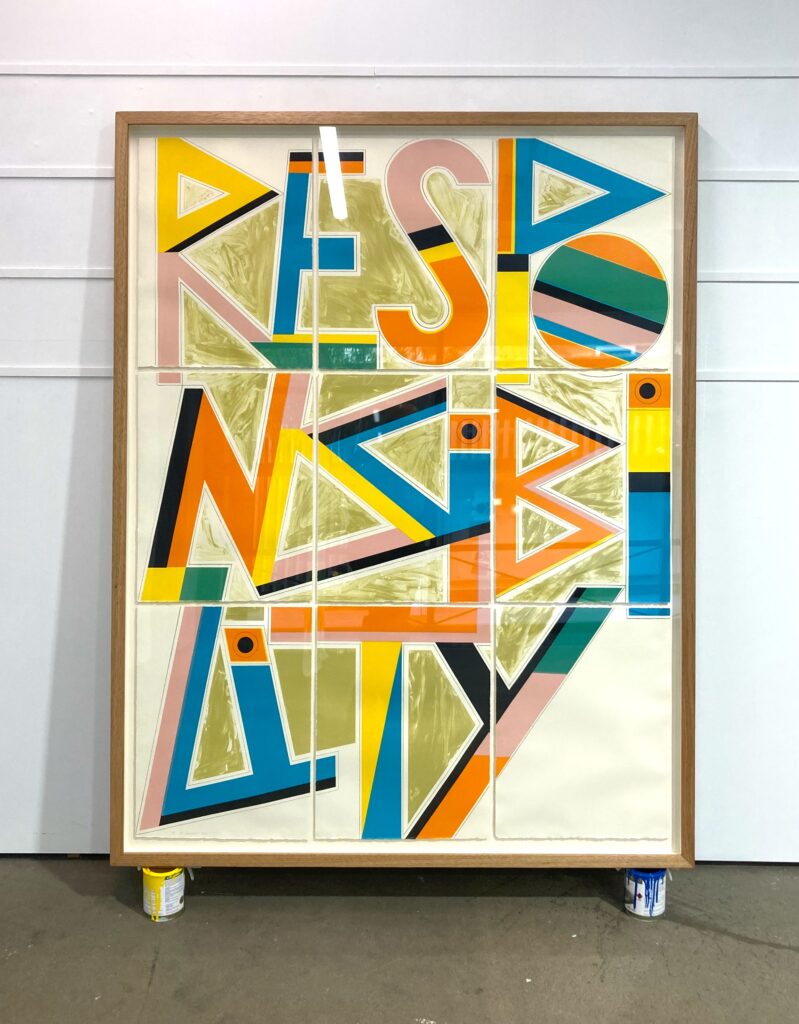

Linda Judge, Birrarung Marr, 2022, acrylic on plastic, 80 x 120 cm

Martin King, tree of life, diary of lost souls in twenty volumes No.1, 2022, etching, drypoint, spitbite, chine-collé, hard-cover books, 120 x 112 cm framed

Olga Dziemidowicz, Celebrating 1029363, 2022, charcoal on Japanese paper, 105 x 120 cm framed

Todd Johnson, 3 weeks, 2 days, 8 hours, 2022, archival pigment print from slide film, 85 x 85 cm

A liveable climate needs trees and trees need a liveable climate…Imagine what the trees themselves would be saying about being exposed to a climate and biodiversity emergency.1

In the early 2000s, the City of Melbourne’s Urban Forest and Ecology Team created an interactive map providing information on every tree ‘managed’ by the City. The map, called Urban Forest Visual, provides details for some 80,000 trees in the City’s streets, parks, gardens, plazas, campuses, river and creek embankments, wetlands, railway corridors, community gardens, green walls, balconies and roofs. Users can click an icon to learn each individual tree’s age, genus and ID number.

Each tree also has an email address.

The map allows the City to keep track of this Urban Forest, an amazing asset that among other things, quietly filters our air and water, sequesters carbon, provides shade, shelter and habitat, and generally makes our urban spaces more inviting, liveable and beautiful. The trees were allocated email addresses so that members of the public could inform the council if a tree needed attention, such as if it was obviously declining in health. What the City did not expect, once the map was made public in 2013, was that people would send the trees emails of thanks, love and admiration. By 2018, the trees had received more than 4,000 emails from around the world. 2, 3

It was this human outpouring, and also ‘…imagining the multitudes of multispecies connections, interdependencies and communications – in the context of the Climate Emergency and the City of Melbourne’s world leading Urban Forest Strategy’4 – that inspired the CLIMARTE5 team to initiate TREE, an exhibition of works focussing on individual trees mapped from the Urban Forest Visual map.

In thoughtful and varied responses, the artists have chosen, as instructed, specific trees from the Urban Forest Visual Map as the subject of a new work. They have then stepped back to consider the personhood of that tree, just as an artist in the ever-popular Archibald might step back to consider how best to portray the individuality of their chosen human subject.

Most traditional among the works are Lauren Guymer’s watercolour, Gum Reflections I, Gum Reflections II, Benedict Sibley’s magnificent charcoal, Citriodora, Rod Gray’s domain, Zahra Marsous’ Light, Shadow and the Pine Tree 1, 2 & 3 and Robbie Harmsworth’s meticulously detailed graphite and coloured pencil Portrait of the Yate.Tree. They pay homage to their chosen subjects, depicting them realistically in all their stately glory. Their artists’ statements elaborate on their choice of subject. Guymer, reflecting on how parks can be managed to enhance urban ecology, twins two Eucalypts that stand in different parts of Royal Park, but are joined by their proximity to wetlands. Sibley has long known his tree, a magnificent Lemon-scented Gum at the northern end of Swanston Street, and its presence transports him to a leafier, greener world. Gray has chosen a vast Moreton Bay Fig, and reflects on the microclimate it creates in its cool gloom, host to legions of smaller creatures. Marsous depicts a Pine, musing on its experience as it stands, watchful sentinel over humans’ passing lives. Harmsworth, whose practice focuses on the fate of Australian forests, has picked the Yate tree, a ‘significant tree’ on the National Trust Register planted by Baron Ferdinand von Mueller, first Director of Melbourne’s Royal Botanic Gardens. Harmsworth writes,

“The magnificent ‘Yate’ tree is 21m tall and has a 2m circumference. The tree is 145 years old, and deemed in poor condition. I felt drawn to make a portrait of this beautiful specimen, particularly in light of its poor health and the question as to its legacy…I am in awe of the tree’s age, height and heritage and with every mark I made over the hours of drawing this beautiful specimen, my relationship with the spirit of the tree deepened. Whilst this is not a photographic representation, through distorting the image, I wanted to express its grandeur and the sense of looking up into its branches to the sky beyond.”6

Less traditionally realist are works by Charlotte Watson, Zoe Haynes-Smith, Janice Gobey, Linda Judge, Martin King, Jan McLellan and Julia Schmidt. King presents a hybrid of two trees from the Fitzroy Gardens, an English Ash and a Lemon-scented Gum, in a cloud of birds and text tessellated across a series of re-purposed open books. As the books themselves are made from trees, King’s work reverberates across histories and media as the hand and eye glance at once across page, bark and etching plate.

In her statement, Haynes-Smith writes that her digital work Tree Medicine’ ‘ll, ‘…pays homage to the magnificent trees that surround the hospitals of Melbourne…Magical in their ability to extend a healing presence, not only to the patients but also those who live and work in Melbourne. Nature, particularly a view of trees, is known to help hospital patients recover faster by reducing blood pressure and stress. Studies found that just 3-5 minutes spent looking at nature can help reduce anger, anxiety and even pain.’

Judge’s Birrarung Marr is painted on a matrix of plastic bread-tags, giving her work a pixilated, glitchy appearance well suited to her theme of microplastics in our waterways. Todd Johnson is also drawn to examine more closely the interplay between his tree and its immediate environment. In 3 weeks, 2 days, 8 hours, an experimental photographic work, the artist has left exposed slide film in the river water near his chosen tree, an English Oak, and also left it to dry outside, so the image is a collaboration with the site.

Standing in contrast to the 2D works is Susie Lachal’s small bronze, environmental justice. Where paper reminds us of our dependence on trees and all that they produce, bronze stands out as an inorganic medium. Ode to an Elm, the bronze was cast using the lost wax process from a structure of twigs dropped by the tree during strong winds in May and June. There is a lovely interplay here of the permanent and the ephemeral, to which Lachal responds, ‘Within colonial values, a bronze sculpture attributes recognition to the bronzee and memorializes the contribution they have made in the world. The resultant object has the potential to open discussion around more equitable relations toward greater environmental justice.’

Other artists have also focussed on specific details of their tree. Olga Dziemidowicz’s Celebrating 1029363 is a charcoal frottage or rubbing of her tree’s bark. The delicate physicality of the resulting marks, made with charcoal on Japanese paper, creates a papery skin, evoking also the quality of elderly human skin aged by time and elements. Dziemidowicz’s concern is that old trees, like old people, are not celebrated in our society. In her work she hopes ‘…to commemorate and celebrate them and somehow capture their mark in order to elevate it and remember the tree that will disappear in the next decade.’ In her work Traces, Bridget Hillebrand also examines the unique skin of her tree, another beloved Lemon-scented Gum, reproducing its tone, pattern and texture through linocut on softly flowing kozo paper.

Michelle Burns and Heather Hesterman focus on their trees’ leaves. In her 6-panelled work Decomposition, Burns meticulously renders the deterioration of an Oak leaf from the deep tones of the recently fallen to a barely-there skeleton. Hesterman was motivated to use a mature Ginkgo tree (‘…a rare fossil…virtually unchanged from the Jurassic period’) in the Flagstaff Gardens as her subject for Tree Project: Ginkgo I, in response to the species’ unfortunate presence on the IUCN’s Red List of Threatened Species. Hesterman has used the tree’s fallen leaves and stems to make both her image and the ink for the piece, enmeshing the tree within the work. She writes, ‘Gingko leaves and bark allegedly have specific medicinal properties. In Tree Project: Gingko I, the tree’s materiality becomes part of the artefact with ink derived from leaves and stems. As the words, ink, and leaves enmesh in this artwork, does the future of Gingko biloba exist only in written and pictorial forms, or will this unique tree species survive another 100 million years?’ Like Hesterman, Barbara Wheeler has also used tree castings to create her work, The Stick Report. With natural dyes made from the same species as her chosen tree, a Smooth-barked Apple or Angophora costata, Wheeler has coloured silk and wool thread to then wrap around fallen Eucalypt twigs – ‘a communique’ she writes, ‘from the Eucalypt nation. Its message is that we are interconnected.’

Nancy Liang has also chosen the ancient Ginkgo as her muse, referring to it as a ‘mythical beast – Face unchanged to developing civilisation and its influences, it appears as it does more than 200 million years ago’. Liang’s poetic work is influenced by traditional Chinese landscape paintings, and reflects how trees are closely tied to the human experience.

Resonating with Dziemidowicz’s frottage and Hesterman’s foliate alchemy, Kathy Holowko and Sarah Moore’s abstract collaborative work is not a drawing of a tree but a drawing by a tree! By attaching markers to the tree’s branches on a windy day, the tree made marks on the paper, capturing a delicate collaborative choreography. Abstraction also allows Erica Elgin in her series of etchings Outside observation I, II and III to convey through colour and gestural mark ‘…the profound emotive reactions experienced when noticing the captivating details of nature present across Melbourne.’ Elgin’s prints at once evoke the texture of bark and environmental turmoil, conveying a sense of both the living tree, its life force and the chaos/unpredictability of its environment.

In many ways the twenty-five works in this exhibition are yet more love-letters, created to thank, celebrate and mark – deeply and expressively – the individual significance of each of these wonderful living creatures that silently enrich our city. TREE spans solemnity and joy as the artists examine the profound significance of living alongside these giant beings that are so easily taken for granted, but which give and mean so much. To spend time with the works is to want to visit these trees and get to know them personally.

—

TREE is on 11-22 October at fortyfivedownstairs, 45 Flinders Lane, Melbourne. Opening event: To be opened by Prof. David Karoly, 6 pm October 11.

Gallery hours: Tuesday-Friday: 12-6pm, Saturdays: 12-4pm, Tuesday and Friday evenings: 6-8pm. Admission: Free

Participating artists Katherine Boland, Michelle Burns, Olga Dziemidowicz, Erica Elgin, Ariella Friend, Janice Gobey, Rod Gray, Lauren Guymer, Robbie Harmsworth, Zoé Haynes-Smith, Heather Hesterman, Bridget Hillebrand, Kathy Holowko & Sarah Moore, Todd Johnson, Linda Judge, Martin King, Susie Lachal, Nancy Lliang, Jan McLellan Rizzo, Zahra Marsous, Jarrad Martyn, Julia Schmitt, Benedict Sibley, Angela Viora (performance), Charlotte Watson and Barbara Wheeler.

TREE is made possible through a City of Melbourne Arts and Creative Investment Partnerships project grant.

—

NOTES

- CLIMARTE website, 2022, TREE project description, https://climarte.org/project/tree-project/

- Burin, Margaret, 11 December 2018, People from all over the world are sending emails to Melbourne’s trees, ABC Story Lab, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2018-12-12/people-are-emailing-trees/10468964

- Go to https://www.abc.net.au/news/2018-12-12/people-are-emailing-trees/10468964 to read some of the emails and see the trees that received them

- CLIMARTE website, 2022, TREE project description, https://climarte.org/project/tree-project/

- Founded in 2010, CLIMARTE is a unique organisation that brings together artists, scientists and the community to discuss and act upon the immediate threat of Climate Change. Governed by a Committee and operated by a management team of voluntary arts professionals, academics and activists, its vision is: ‘To harness the power of the arts to communicate the Climate Emergency in all its manifestations thus mobilising the public to demand immediate effective action; a transition to zero emissions while at the same time drawing down legacy carbon at emergency scale and speed, before 2030.’ https://climarte.org/about-us/

6. Artist’s statement, 2022, Climarte website https://climarte.org/project/tree-project/. All quotations from the artists are from this source.

—

Join the PCA and become a member. You’ll get the fine-art quarterly print magazine Imprint, free promotion of your exhibitions, discounts on art materials and a range of other exclusive benefits.