Above:

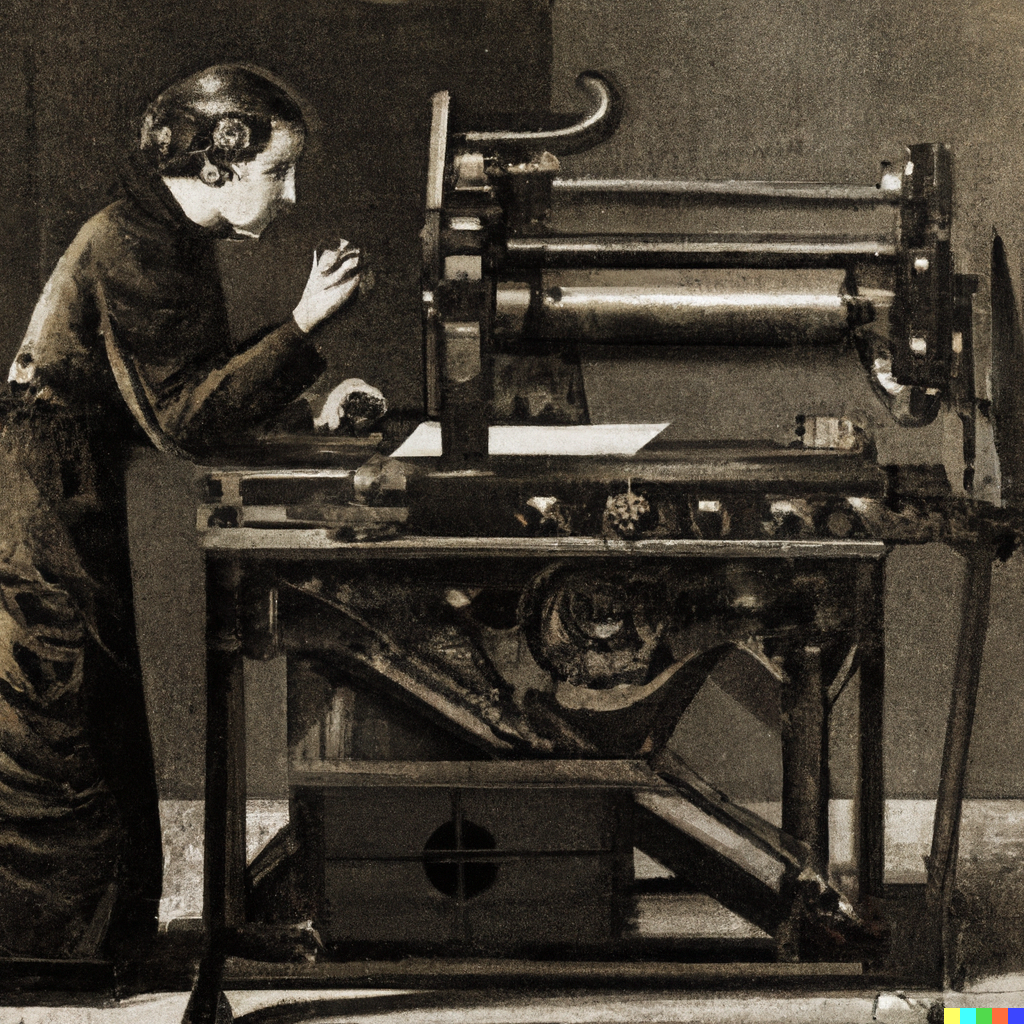

Sarah Robinson, Impossible Machine (i): A Sense of Touchwood Lithography (2023), RGB digital print, Sarah Robinson instructing AI, 1024 x 1024 pixels. Image courtesy of the artist

Below:

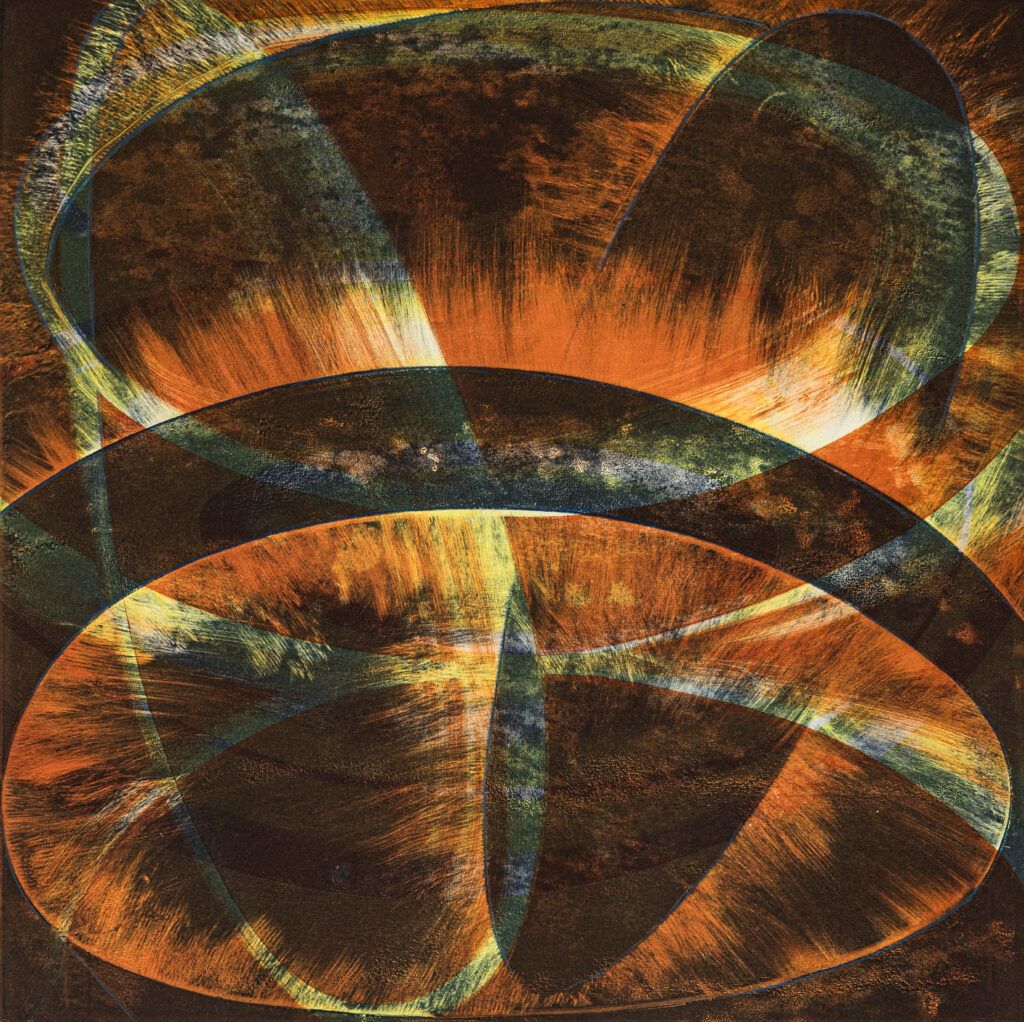

Monika Lukowska, Impossible Marks (i) (2023), Monika Lukowska x DALL-E, digital print, 36 x 62 cm. Image courtesy of the artist

Monika Lukowska Impossible Marks (ii) (2023,) Monika Lukowska x DALL-E, digital print, 36 x 62 cm. Image courtesy of the artist

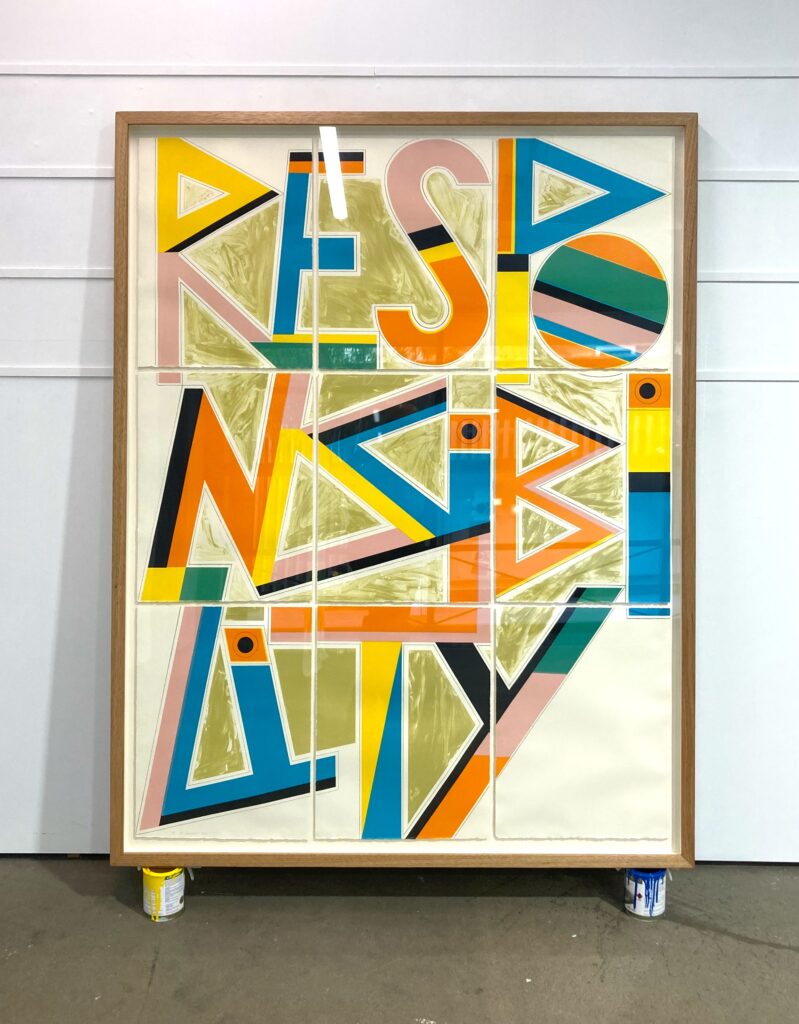

Sarah Robinson, Homage to John Baldessari Art by telephone instructions “Take a 16mm movie projector and put it on the wall at a distance that makes 6 x 8 taped rectangle on the wall” (2023), AI, digital print 30 x 20 cm. Image courtesy of the artist

An Improbable Contest Between an Authentic Touch and the Digital, (2023), Sarah Robinson x DALL-E2, digitally manipulated print derived from an original woodcut, Awagami paper, 29.8 x 21cm. Image courtesy of the artist

TRANSMEDIAL: AI in PRINT draws its premise from a 1969 seminal conceptual exhibition, Art by Telephone1 (ABT), at the Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA) in Chicago where artists such as Richard Serra, Sol LeWitt, John Baldessari and Richard Hamilton amongst others, instructed the gallery curator via telephone on how their artwork should be made. In our contemporary take, Generative Artificial Intelligence (GenAI), the latest technological invention, is utilised in artistic collaboration replacing the telephone. We question the implementation of the human touch involved in traditional printmaking through the digital lens by exploring printmaking concepts and themes that emerge within our communication process with Artificial Intelligence (AI).

Prepare to be captivated by \”The Art of Touch,\” a masterpiece that transcends pixels and

pixels, weaving together a symphony of tactile experiences.[1]

In the original Art by Telephone exhibition, the artists’ instructions were dictated by phone to the MCA gallery curator for his staff (the labour) to execute the production of the artworks. Rather than using people (labour) to generate our work, we asked AI to follow our instructions which investigated themes of materiality, the history of printmaking, printmaking techniques, and tactility. The results were printed and further transformed by wood and paper lithography, and woodcut. Art by Telephone, ChatGPT, and DALL•E 2 operate under predetermined rules and actions. Integrating AI as a tool and image generator in blending our work, Transmedial: AI in Print examines the concepts and ideas that emerge within the communication process using contemporary technology.

In 1969 phone technology was used as a link between the artists’ concepts and the executing labour of the gallery staff. For us, AI serves as a link between our instructions and mind–guided image manipulations–subsequently modified by hand, through paper lithography and woodcut methods. The images that emerged from AI’s data-scraping system came with abrupt societal bias and a literal interpretation of words into images. An image portraying an ‘impossible printmaking machine’ with an affinity to the wrought iron printing and weaving machines of the First Industrial Revolution emerged all too easily. Through a Google Reverse Image Search, images of such machines exposed visual connections of the possible AI training data sets.

Set amongst Luciano Floridi’s 2 acknowledgment that we are now in the Fifth Industrial Revolution (5.0) we set out a framework to consider how the AI images for Transmedial: AI in Print were constructed. For example, a simple error of omitting a space between the words ‘touch and wood’ led to DALL•E 2 creating an image of a woman using touchwood (associated with a fungus) as tinder to create a spark over an impossible machine. This machine incorporates Tudor wood carving and a tinder box underneath the printmaking press, This machine incorporates Tudor wood carving and a tinder box underneath the printmaking press, which further conceptualises images of impossible machines as a comment on the rise of nonsensical AI images.

Furthermore, in observing these AI generated images, some could easily be indecipherable from an artwork created by an artist’s hand. Jonas Oppenlaender remarks that ‘Text-to-image generation could lead to a depreciation of the value of art and the human virtues encoded in such art.’ 3 In ABT, artists gave specific instructions to the MCA curator and staff resulting in meticulously executed artworks. Yet our instructions to AI yielded a multitude of bizarre images that go beyond this human-to-human process. In our investigations, DALL•E 2 turned out to be only as good as its training data set, aligning with Lev Manovich’s statement that, ‘A neural network does not understand what it generates.’ 4 While ChatGPT recognises language patterns and statistically predicts what word comes next, as creative thinkers, and out of necessity we rapidly become the ‘human-in-the-loop.’ 5 Reflecting on rather plain and unsatisfying images prompted us to bring traditional printmaking to the process to embed the sense of touch. Initially, we attempted to add our ‘human touch’ through typed instructions into DALL•E 2, such as a “sense of touch woodcut print” or “mark[s] making with the tushe on the lithographic stone using a brush”. As artists, we intervened, achieving a sense of touch and Oppenlaender’s 6 human integrity by admittedly scanning images and manipulating hand-drawn marks or woodcut blocks back into the AI production line. We had become curators of information, and considered permanently removing the added original handmade marks in the images, keeping the original AI ones!

However, as AI ‘…has no knowledge of the world, or history or contemporary culture.’ 7 what was the benefit of this editing? Or are we destined in the future to only see the real world through digital data dredging? In fabricating selected AI images by hand through woodcut and lithography processes, drawing from a haptic experience of traditional printmakers, we argue that AI was an enactment of our concept.

We returned to the original ABT show’s premise, exploring a collaborative aspect of art creation and the interaction between artists and technology. ChatGPT was used to select artist John Baldessari from the original MCA exhibition; instructions from his original recording 8 were inputted into DALL•E 2, creating new images that could easily be mistaken for a contemporary hi-tech media installation. Indeed, by using AI as a tool, AI can offer conceptual expansion in creative practice, as it is fair to say that keeping a ‘human-in-the-AI-loop’ offers contemporary printmakers the best tactic to preserve their traditional printmaking skills.

Laszlo Moholy-Nagy ‘…emphasized the role of the modern artist as a producer of concepts rather than a craftsman physically involved in the making of the work.’ 9 This statement, challenging traditional art making, still holds its relevance in the age where increasingly images are impartial instructions by artists yet generated by machines. There is a fear that in the realm of the Industrial Revolution 5.0, traditional printmaking skills will be lost, and the haptic values of prints will diminish in contemporary image-making. Our knowledge of the world as living, breathing beings shapes how we use generative AI in printmaking in a ‘manner that preserves and enhances human creativity rather than overshadowing it.’ 10 The exhibition initiates a dialogue on the role of AI in contemporary printmaking image-making and our reliance on emerging smart technologies.

A repurposed 1960-70s UK telephone for Transmedial: AI in Print pays homage to the original show. The audience is invited to leave a recorded three-word message to describe what printmaking is to them. These three words will instruct AI to create new images to capture the contemporary outlook on the field of printmaking. The aim of using audience-directed images is to create an impossible manual of printmaking designed for a future of nonsensical printmaking. This manual gives insights into an unfortunate imagined future direction in contemporary printmaking: a future moving away from the human touch, traditional skills, and creatively responsive actions. As artists, we must hope this never happens.

NOTES

- https://mcachicago.org/Exhibitions/1969/Art-By-Telephone

- Floridi, Luciano. (2023). AI as Agency Without Intelligence: on ChatGPT, Large Language Models, and Other Generative Models. Philosophy & Technology. 36. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13347-023-00621-y.

- Oppenlaender, Jonas, Johanna Silvennoinen, Ville Paananen, Aku Visuri. (2023). Perceptions and Realities of Text-to-Image Generation. 279-288. https://doi.org/10.1145/3616961.3616978.

- Manovich, Lev. (2023). Towards “General Artistic Intelligence” Retrieved from https://www.artbasel.com/stories/lev-manovich

- Eloundou, Tyna, Sam Manning, Pamela Mishkin, Danie Rock. (2023). GPTs are GPTs: An Early Look at the Labor Market Impact Potential of Large Language Models.

- Oppenlaender et al. 2023

- 7. Oppenlaender et al. 2023

- https://www.ubu.com/sound/art_by_telephone.html

- Publication excerpt from MoMA Highlights: 375 Works from The Museum of Modern Art, New York(New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2019).

- Oppenlaender et al. 2023

[1] The artists acknowledge use of Generative Pre-trained Transformers (GPTs), Large Language Models (LLMs), and Generative AI in this project.

—

Transmedial: AI in Print, is at the PCA Gallery, 23 January-9 February.

STUDIO 2 GUILD, 152 STURT ST

SOUTHBANK, MELBOURNE. OPENING HOURS: TUESDAY-FRIDAY, 10AM – 4PM

—

Join the PCA and become a member. You’ll get the fine-art quarterly print magazine Imprint, free promotion of your exhibitions, discounts on art materials and a range of other exclusive benefits.