Sydney Printmakers: Sasha Grishin

Sasha Grishin writes about the first fifty years of Sydney Printmakers, ahead of their sixtieth anniversary in 2021. The exhibition Sydney Printmakers 2020 is presently showing at May Space by appointment until April 24.

20 April, 2020

In Exhibitions,

Printmaking, Q&A

From top:

Anthea Boesenberg, House, 2020, monotype on paper, wax, electrical fitting, timber base – unique, 35 x 28 x 28 cm

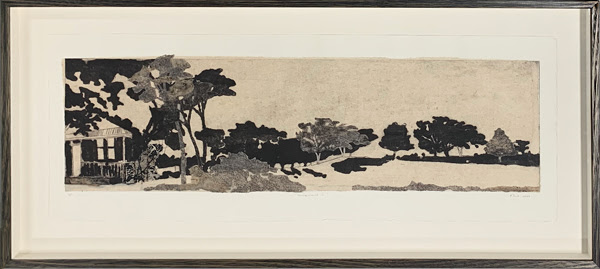

Karen Ball, Homeward, 2019, carborundum etching, drypoint, chine-collé, collage (unique state), 22 x 75 cm

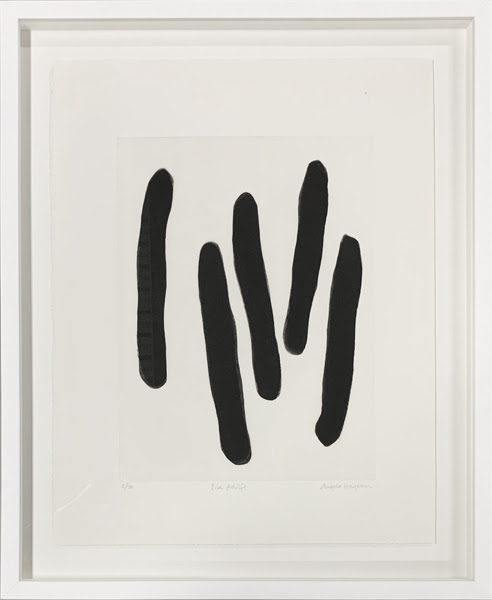

Angela Hayson, Five Adrift, 2020, etching, 40 x 30 cm (unframed), 64 x 54 cm (framed), edition of 20

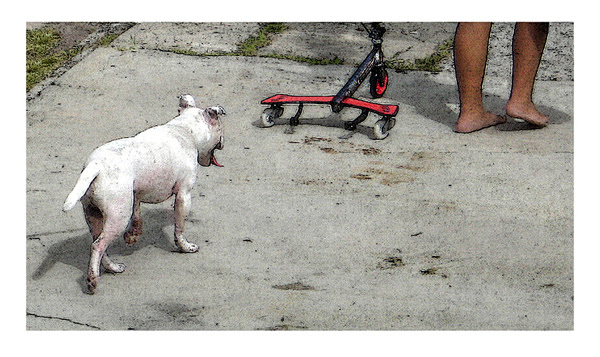

Marta Romer, Red Scooter, 2017, archival pigment inkjet print, 28 x 38 cm (unframed), 36 x 48 cm (framed), edition of 10

Carolyn Craig, Words Between Bodies (swearing as social capital), 2020, laser etched timber, 3D printed plastic, perspex shelf (three pieces), 26 x 42 x 14 cm, etching size 22 x 13.5 cm, 3D print size 11 x 14 x 2 cm

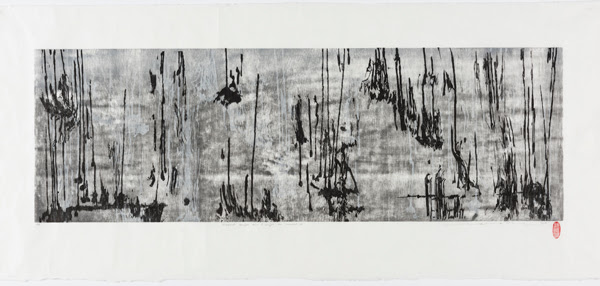

Seong Cho, Moment Seized Me, I Seized The Moment VIII, 2018, woodblock print, 62 x 144 cm (framed), edition of 5

Susan Baran, Alhambra Palace, 2019, photopolymer (solarplate), intaglio, 55 x 120 cm

This essay was first published for Sydney Printmakers’ fiftieth anniversary.

Sydney Printmakers is a unique phenomenon in Australian art with few parallels anywhere in the world. Although numerous exhibiting associations of printmakers have cropped up from time to time in Australia, what distinguishes Sydney Printmakers is three things. Firstly, no other exhibiting organisation of printmakers has so effectively represented the best printmakers of a city and has done this so comprehensively. Secondly, no other organisation of printmakers in Australia has managed to sustain itself independently over such a prolonged period of time without becoming a de facto filial of an institution, such as an art school. In other words, Sydney Printmakers have remained truly independent. While thirdly, no organisation of printmakers has managed to survive for fifty years without extensive periods of dormancy.

The question immediately arises as to why this should be the case. The answer to some extent must lie in the historic peculiarities of printmaking in Sydney in the immediate post-war period. In Adelaide and Melbourne, printmaking gained an early institutional base in art schools and in technical colleges, whereas the situation in Sydney was quite different. Until 1964, when Earle Backen began to teach etching at the East Sydney Technical College, printmaking was not taught in Sydney art schools. Even then, initially there was only a small etching press and a class of nine students; in the late sixties a larger Japanese etching press was obtained, and lithography was introduced in the early seventies. It was this lack of institutional support for printmaking in Sydney that was partly compensated through community action. The Sydney Printmakers formed in 1960 and held their first exhibition in 1961. Their purpose was that of an umbrella organisation for exhibitions and the dissemination of information about prints and their creation. From the start they became the principle forum for printmakers in Sydney and have continued to play a constructive role through to the present day. Workshop Arts Centre in Willoughby was established at about the same time by Joy Ewart with assistance from fellow artists and supporters and came into being in response to the same circumstances, to compensate for a lack of printmaking facilities at art schools, and it too has continued to flourish through to the present. This popular and democratic basis for the Sydney Printmakers, their independence, and the fact that they had to meet a real need in the artistic life of Sydney have been a crucial part of its dna and to some extent explains its longevity.

Although printmaking goes back centuries, like most art forms it enjoyed periods of popularity and periods of relative neglect. In post-war Australia, by the late 1950s and early 1960s, printmaking was enjoying an unprecedented popularity and was attracting the most exciting young talent of its day. It was also supported by committed print curators working in the state galleries, especially in Melbourne, Adelaide and later in Sydney, and was encouraged by the acquisition of modern prints by these institutions and by touring print exhibitions. The tradition of the modern print which emerged at that time brought together relief printing, intaglio, lithography and screenprinting, all under the one roof, and in this broke with the specialised cottage industry mentality of earlier decades. Printmaking in the 1960s had easily eclipsed the early popularity of the refined intaglio prints of the Painter-Etchers’ Society or the subsequent popularity of the hand-coloured relief prints produced largely by its all female cast. Printmaking in the early 1960s, when the Sydney Printmakers came into being, had a boldness, confidence and challenged for supremacy all of the visual arts. For example, the Lithuanian-born printmaker, Henry Salkauskas, who played such a significant role in the formation of the Sydney Printmakers, on settling in Sydney in 1951 was shocked to discover the low standing of printmaking in Sydney and “he viewed this low esteem for contemporary Australian prints as a kind of personal challenge, which he would do his utmost to reverse.”[i] By 1963 he had won the grand prize for the Mirror-Waratah Festival in the open section with a screenprint edging out the paintings and sculptures which were competing for the same award. This was the first ‘golden age’ of Australian printmaking and the first ‘golden age’ of the Sydney Printmakers.

By the 1980s and into the 1990s printmaking in Australia in general, and in Sydney in particular, became somewhat institutionalised and lost some of its earlier gloss, excitement and prominence as an art form. A number of artists saw a more viable alternative in the poster collectives and turned their backs on the printmaking workshops at art schools, while others abandoned printmaking altogether and turned to painting, installation art or photography. Also, fewer of the younger outstanding students chose to major in printmaking. The second wave of the printmaking revival of the past decade, which we are still experiencing so strongly today, had its catalyst in a number of quite disparate circumstances which included waves of inspiration from Asia; a bourgeoning print market which was in part inspired by the artistic and commercial success of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander prints and, perhaps most significantly, the absorption of new technologies into printmaking. Printmaking has always been the most technologically adventurous art form. It was the first to embrace the printing press in the fifteenth century, the first to embrace lithography in the eighteenth century, the first to embrace photography in the nineteenth century and the first to embrace digital technologies in the twentieth century. This remarkable ability to constantly reinvent itself has ensured its continuing relevance and vitality. This is not to suggest, even for a second, that the most interesting prints today are those which employ computer technologies, but rather that the new wave of interest in printmaking in general, generated by some of these circumstances, has led to a revitalisation of the whole art of printmaking. Printmakers no longer feel that they are marginalised and participating in an art form that somehow sits on the periphery of so-called serious mainstream art, but instead they have quickly realised that they have front row seats in the emerging developments of contemporary Australian art.

Sadly, in Sydney, this has not been reflected in a commensurate growth of commercial art galleries specialising in prints, in fact there seem to be fewer of them today than a generation ago. Nor has there been a growth and expansion of institutional printmaking departments, but if anything, a slight contraction despite some exceptionally talented and committed staff. This has meant that the Sydney Printmakers today has an even a greater relevance and significance than at any time in its history. There is also a richer diversity of printmakers working in Sydney today than perhaps at any stage in its history.

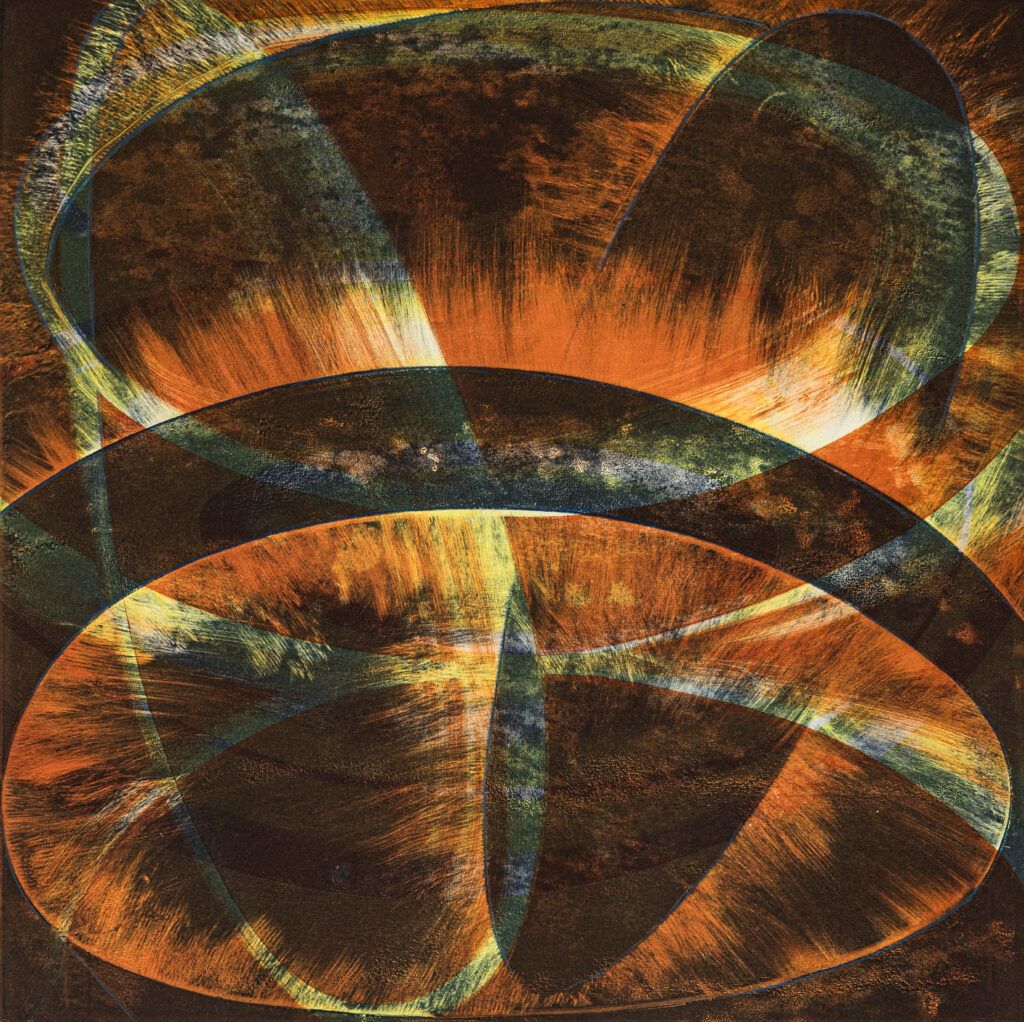

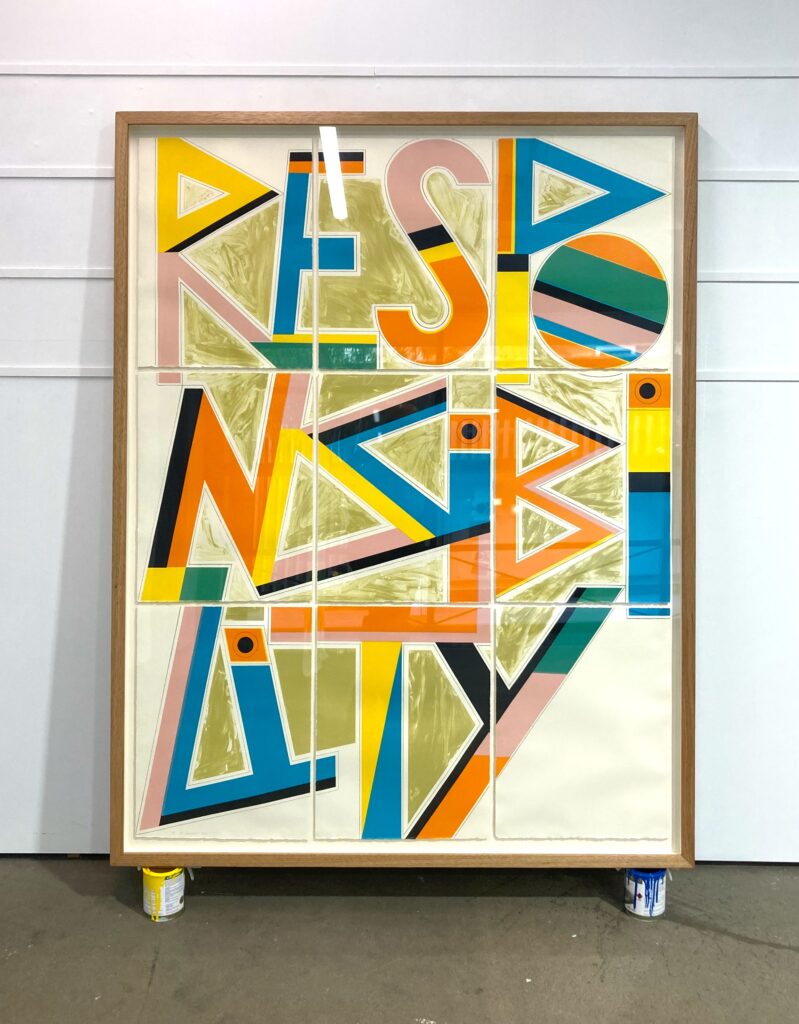

The Fiftieth Anniversary exhibition of the Sydney Printmakers is not simply a show that demonstrates the activities of most of the members of this organisation, but it can also be viewed as a report card on the state of printmaking in Australia. What is particularly attractive is the complete lack of dominance of any single style, medium or prevailing theoretic orthodoxy. Like the broader Australian printmaking scene, the Sydney Printmakers in this exhibition have embraced the widest possible range of printmaking technologies. In an exhibition of about fifty-six artists I could count over twenty different printmaking technologies or better termed printmaking mentalities. These include intaglio work, with a mixture of etching, drypoint and aquatint, lithography of various types, wood engraving, screenprints, collagraphs, stencils, stamps, woodcuts and linocuts, frottage, carborundum, digital etchings and inkjet prints, monotypes and monoprints, box assemblage, various species of photopolymer printmaking, not to mention such elaborations such as chine collé, à la poupée, hand-colouring and any and every possible combination of the above. To those outside the printmaking fold these terms may appear as mysterious as the incantations of the witches in Macbeth, but for the printmaker this is all perfectly normal – she is also likely to ask “is it on a Velin Arches 300 gsm?” This is only to say that printmakers have their own technical language that cannot be said in the same way of painters, sculptors or even installation artists. There is a tribalism that informs printmaking, in part reflecting the often collaborative nature of the practice and also in part reflecting the perceived minority status of the art form which encourages printmakers to band together with a sense of messianic zeal. I suspect that without this tribalism, Sydney Printmakers would not exist.

As with any ‘art society’ exhibition there is a considerable variety of standards in the exhibition, but I would state categorically that there are no bad prints here. This stresses another role of Sydney Printmakers, that of a quality control organisation, one that permits widest diversity, but imposes standards of competence and professionalism. However there are a number of exceptional prints in this exhibition, works which would look competitive in any international exhibition of printmaking. Roslyn Kean, for example, has the amazing ability to enrich an ancient tradition which she has mastered and make it contemporary and personal. Her Black bamboo and Japanese Garden I are works of serene meditation yet have a wonderful sense of presence. I never cease to be amazed with the inventive genius of Ruth Faerber’s art conceptually and in technique, as brilliantly demonstrated in the digital inkjet prints from Life on the edge series, which explore art as autobiography, but on a new level. They are prints with a very rich cultural resonance. Ruth Burgess, another veteran artist, albeit from a younger generation, also manages to tap into earlier traditions to make a very personal statement. Moving into the delicacy and intricateness of the wood engraving technique, in her The source and Forest quartet, she creates highly intimate statements like a diary of a blue gum forest seen from the canopy.

Gary Shinfield also achieves a sense of intimacy in his work, but uses a straight etching technique in his Enclosure to chart a sense of personal discovery, an encounter with enclosed spaces and their public and private symbolism. In a curious way Susan Baran in her Tsar candelabrum and Thonet chair juxtaposes images from different worlds of visual arts and design to create a startling image of considerable presence realised as a solarplate etching.

A number of artists effectively explore codes or scripts, for example Anthea Boesenberg in Text, a transfer monotype, evokes traces of a mysterious inverted script to which life is given. There is also a wonderful etching by Christina Cordero, Tone poem, which I read as a very personal whimsical script which pays homage to both Miró and Klee yet makes a personal and original statement with the ink bled into the paper as the chine collé is applied on heavy kozo paper. Sandi Rigby’s Traces of text brings together scripts like pages in an artists book realised as linocuts, each with its own unique identity, while Marta Romer’s digital print, Paula tells the story, submerges the portrait within a sea of text.

The landscape remains of crucial importance to many of the artists in this exhibition. Edith Cowlishaw is an unrepentant romantic who in her etching Nightfall, celebrates the mystery and intricate preciousness of the Australian bush, while Tanya Crothers, working on quite a large scale in her hand-coloured collograph, constructs in her Shadows on the plain quite a striking yet lyrical image. Mieke Cohen’s Day 3 – ten days in a tent etching is a diary of travelling within a landscape, that of central Australia. Salvatore Gerardi, working on a monumental scale, in his Nocturne Suite from the Series Tidal Crossings, combines intaglio and relief techniques to create a very evocative piece which serves as a diary of a landscape made across the shape of time. Nathalie Hartog-Gautier in her woodblock print, Hill End 1, employs the actual materials found in the landscape and weathered by the elements to create meditative images evocative of the landscape from which they arose.

For a number of outstanding printmakers in this exhibition, the human figure and the urban environment continue to play a central role. Barbara Davidson in her etching and collagraph Grandstand 2 creates a magnificent portrait of a cross-section of humanity and of Australian patterns of social behaviour. Rew Hanks employs the simplest of techniques of a linocut in King Bungaree and the Bottle Tree to create a most complex iconographic narrative dealing with post-colonial readings of Australian history, while Michael Kempson in his etching Gentle persuasion combines irony, vernacular humour and clever a visual invention to create a memorable icon dealing with the Australian urban environment. Esther Faerber’s digital print, Upon reflection, effectively explores a slightly edgy urban reality. Almost in complete contrast, Rose Vickers creates in her hand-coloured etching, Window, a self-referential world of tranquillity, where beloved objects imbue a space with personality. Jan Melville most effectively assembles a seed box of different female identities. Janet Parker Smith’s urban reality, explored in her screenprint She owl (The intellect), creates a world of the uncanny where in the words of Katsuhiro Otomo’s cult film Akira the characters seem to utter “we don’t belong in the outside world”. Madeleine Tuckfield-Carrano’s digital print Cloud runner imbues an object from the artist’s life with a symbolic presence, like the enigmatic “rosebud” in Citizen Kane, while Seraphina Martin, combining collagraph, drypoint and stamp, in her Finding inner depth creates a very subtle work which can be read on different levels from a comic aside through to an exploration of the human condition.

A number of other prominent printmakers adopt less figurative imagery. These include Carmen Ky, whose digital etching triptych Ripple combines natural forms to express psychic states, Wendy Stokes in her Layered reference xvi plays with the pattern of ocean currents as a metaphor for patterns of being, while Andrew Totman in his etching Without boundaries in a lyrical manner draws parallels between patterns in nature and human sensations.

If there was more room more comments could be made concerning some of the other remarkable prints in this exhibition, but enough has been said to make the point that this is an outstanding exhibition by a dedicated female-dominated cast of printmakers who are continuing to make an important contribution to printmaking in both Sydney and Australia.

Professor Sasha Grishin AM, FAHA

The Sir William Dobell Professor of Art History

Australian National University

[i] Gil Docking, ‘The prints of Henry Salkauskas”, Art and Australia, vol 20/2, 1982, p.193

view exhibition online mayspace.com.au

Open by appointment, Tuesday to Saturday 10-5, at 409b George Street Waterloo. To make an appointment: please call 02 9318 1122 or email info@mayspace.com.au