Superpowers #2: Three Hundred and Sixty-Five Days Under the Sun

words by Eugenia Flynn

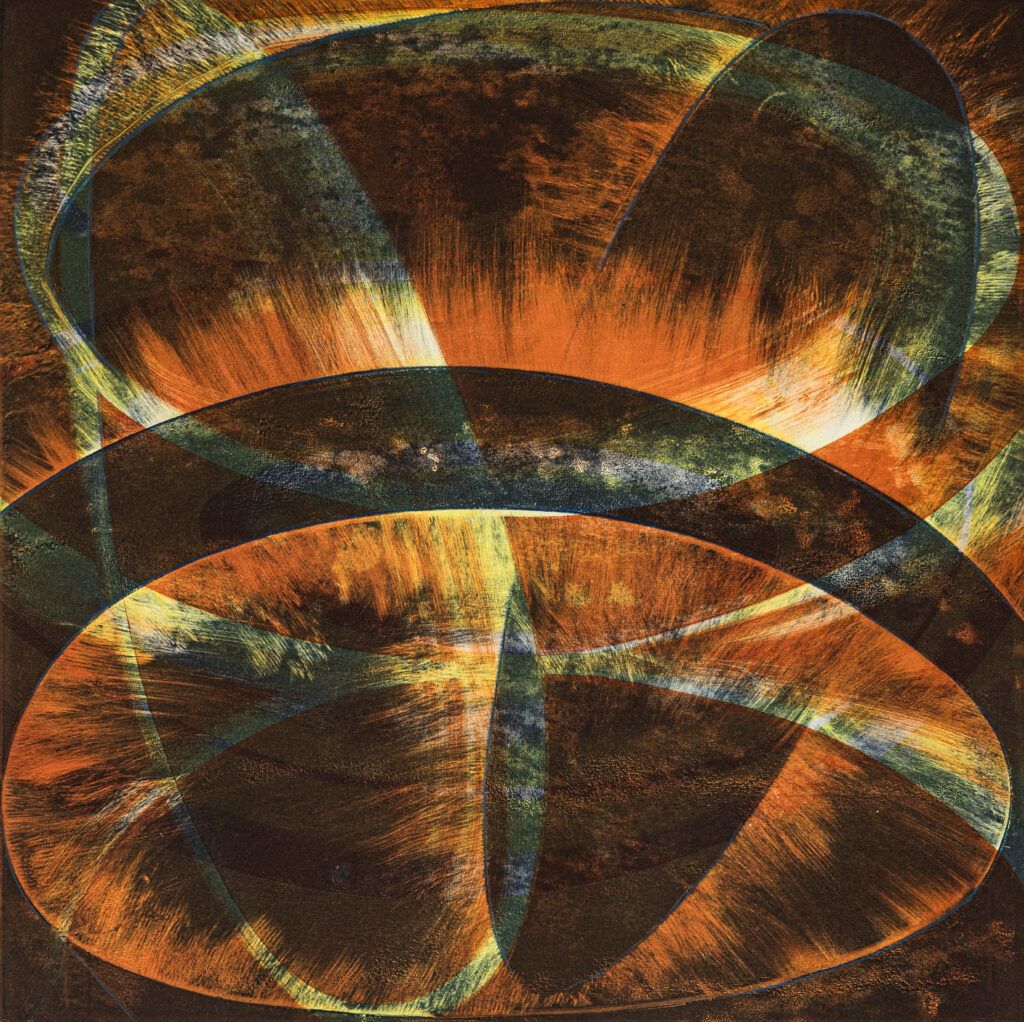

artwork by Yasbelle Kerkow

Following a successful grant application to Creative Victoria, the PCA’s landmark Superpowers project involves four print-media artists teamed with four writers, working in pairs. Each group has been exploring one of four different forms of ‘energy’ – air, sun, water and plant-life – in the context of the global climate emergency, and informed by Indigenous heritage and knowledge.

The essays and artworks created for Superpowers are being published in Imprint over twelve months, and exhibited in due course.

In the second of these four specially commissioned essays and artworks, writer Eugenia Flynn and artist Yasbelle Kerkow contemplate ‘sun’.

13 November, 2020

In Exhibitions,

Printmaking, Q&A

From top:

Australian Inc. Photography: Georgia Steele

When Yasbelle Kerkow and I meet for the first time, it is because Imprint has brought us together. We talk about art and writing and a teeny bit about what it means to be Indigenous. Me, Aboriginal, a little bit older. Her, Fijian, and a little bit younger. Thrown together at last, after multiple missed points of connection. A housemate here, an event there; now, we have this thread between us. It is faint to the eye and slight in nature, slack and flexible, all of the time. Yet it is entirely unbreakable, such is its strength. This thread hangs between us, spanning the distance across the suburbs of Melbourne, swaying slightly in the air at times, gracefully grazing the ground in other moments.

What is this thread between us? Three hundred and sixty-five days and the globe circles the sun once in its entirety. Circle the sun thousands of times over and that is how long both our Ancestors have lived on their respective lands across the globe.

Shared womanhood, shared global indigeneity, common connections to land and seas and skies. I read the collaborative words of Yorta Yorta curator and writer Kimberely Moulton and Sāmoan curator and artist Léuli Eshrāghi and think of the thread between us:

…we consider Ancestral materiality, intellectual traditions and expressions spanning the great oceans, skies and lands connecting the kin and Country of First Peoples from around the world. We see the artistic, economic and cultural paradigms as a reflection on life and death, on black holes and shining stars illuminated as constellations in the night skies from the times of our Ancestors and traced in the footprints made on the lands we travel. In so doing, we ardently love and connect with our kin, known and not-yet-known, human and beyond-human, recognising commonalities and differences as we fight for the continuation of cultural practices.[i]

Yasbelle and I, we share in our respective indigeneity. It informs our work but is not defining in the way the white art world—the world of museums and galleries—perceives it. We define our work on our own terms. Contemporary art and literature, our perspectives, crafted beautifully.

That first time we meet, we sip our drinks—I eat some light brunch—and we talk about orientations of time. How the sun dictates the seasons, the blooming of the earth, and the breeding of the fish. I think of Wiradjuri writer and academic Jeanine Leane on representations of time in the novel Carpentaria by Alexis Wright:

It collapses time and space to honour Aboriginal past, present, memory, future and the sense of collectively experienced time… Wright reconfigures conventional meanings of time and timeless in a story of Aboriginal realism. More specifically, it is Waanyi realism as the story is born of Waanyi times and place and the Gulf of Carpentaria is a place for all times and memory—not just the last 225 years.[ii]

Three hundred and sixty-five days under the sun, circling. Times that by the thousands and it is thousands of generations of First Peoples, defining time by the changing of the seasons, signaled by changes to the land, sky and sea. The earth circles the sun and the flowers grow, bloom and die in an endless cycle that loops and circles just as earth does the sun. Viewed in this way, time ceases its linear march and enters into a different rhythm that encompasses the past, present and future, memories and imaginings. Yasbelle and I, we sit in the coffee shop and we talk about our time, driven by the sun and the seasons and the furling and unfurling of the earth. Time unconstructed by humans.

The next time we meet, we sit, holding our breath and our tongues. We wait for the whitefella to go to the counter, breathe out and have quick, sharp conversations, furtive in nature. Quick, before the whitefella comes back! We drink some water, talk about cultural connections, saqa, and printing on fish skin. It is a for-us conversation that we do not even realise we have been waiting to have. Waiting for snatched moments of privacy, for a few moments of intimacy, born of our global kinship, bound together by the thread draped between us.

Yasbelle tells me about her exchange with an older woman from Turtle Island, while on residency in Aotearoa. How she was taught to process fish skin, something done on coastal homelands across and up the Pacific. A stillness settles over me and I think of First Peoples around the world, connected by the skies, the oceans and the lands. I see the women of coastal communities, standing in the waters at the edges of the oceans, tiny figures under the great expanse of the arced blue skies. I envision them standing inland, processing fish skins, this time for print.

We talk more about women’s work. Our art, our culture; the past and the future. I prompt and Yasbelle tells me about her family. The women and their weaving, cultural safekeeping, reclamation and resurgence. She is quick to remind me that her own art is connected, but different. I am reminded that Yasbelle makes art on her own terms. Unapologetically so. Innately Yasbelle.

I think back to a piece I wrote a few years earlier:

This is why I view all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander artistic and cultural practice as sites of resistance. Every story that is told, whatever the artform, can be viewed as political. As embodiment of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander identity and culture, no matter whether the shared story is light-hearted or politically hard-hitting, Indigenous arts and culture draws a line in the sand. It asserts Indigeneity, what it means to be Black, and in doing so resists the hostile dominant culture, that which seeks to silence and undermine.

That these stories are so often shared unapologetically is also a form of resistance. Many non-Indigenous visual and performing arts critics will pigeon-hole Indigenous works as educational, part of the reconciliation process, never realising that they centre themselves as the non-Aboriginal audience, the raison d’être. Quite the opposite, most Indigenous works typically hold a space of autonomy, viewing Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities as the primary audience and thereby creating more authentic works that can then attract a wider audience.[iii]

I listen to how Yasbelle quietly asserts her artistry. How I try to push the agenda I have in my head upon her; my intellectual interests in her work, my ideas of Indigenous contemporary art. Sitting together in yet another café, Yasbelle sets me straight and I retreat, knowing I have crossed a line.

The next time we speak, we talk on the phone. The fish skins are almost finished now and Yasbelle describes them as prints of simple block designs, drawing on her heritage. She tells me about printing in Horsham and the processes of her work, and eventually we get to talking about the way we value our own practice, as artists, as First Peoples. Yasbelle does not want others to push their ideas of the ‘traditional’ onto her work, she does not want to explain her work. She just wants to be.

I just want to be, too. I think of my practice: written, in English, far from ‘traditional’. I think of the supposed juxtaposition of ‘traditional’ and ‘contemporary’ and non-Indigenous constructions of indigeneity. Yasbelle’s quiet assertions remind me that our cultures evolve and adapt. That they had to adapt in order to survive the cultural genocide of colonisation. That so-called ‘traditional’ and ‘contemporary’ art are part of one culture. That one is not more true or authentic than the other.

My resistance—Yasbelle’s resistance —through culture. Contemporary expressions of long-living cultures, not versions of culture interpreted by anthropologists or art historians and deemed to be ‘correct’. This is a resistance that learns from the past and imagines endless possibilities for the future. I think of Cherokee academic and writer Daniel Heath Justice, writing about Why Indigenous Literatures Matter:

I suggest instead that ‘wonderworks’ is a concept that offers Indigenous writers and storytellers something different and more in keeping with our own epistemologies, politics, and relationships. It’s a term that gestures, imperfectly, toward other ways of being in the world, and it reminds us that the way things are is not how they have always been, nor is it how they must be. It’s in Indigenous wonderworks that some of the best models of different, better relationships are being realized, and it’s these stories that give me hope for a better future, even in these scary times. In short, I think wonderworks help us become better ancestors, as they allow us to imagine a future beyond settler colonial vanishings, a future where we belong.[iv]

I think of Yasbelle’s art, my writing, and the creative imaginings of First Peoples, connected across the lands and the seas. I imagine us all, looking up at the great blue arc of the sky, imagining futures beyond our current existence, creating wonderworks that move us past the shared experience of contemporary disaster.

Three hundred and sixty-five days and the sun patiently waits. The Earth circles, and I sit, waiting, thinking. Out of balance, the Earth warns us with raging fires and drying rivers. With temperatures rising and changing climates, the earth circles the sun, and this time it is off kilter. I think back to Yasbelle and the sun dictating the seasons, orienting our time through its relationship to the blooming of the earth and the breeding of the fish. The sun, sitting in perfect balance with the sky and the land and the seas and the rivers. The sun, working in harmony with the air, earth and water to create a perfect balance and a rhythm by which we can orient our time.

I remind myself that the sun has been patient for millennia. The earth circles, the moon waxes and wanes, but the sun is constant. The sun, it waits. For the earth to finish its rotation. For us humans to stop creating imbalance. For time to turn back to its natural orientation. The sun waits and the land, the sky and the waters heat ever so slightly. Now out of delicate balance, the land clears itself of animals, the sky rids its blue expanse of birds, the water purges fish from its depths. I think of Yasbelle and her simple block designs, of women standing on the edges of great oceans, waiting for the fish to be able to continue their work. Fish that never come because the earth is out of balance with the sun.

The last time Yasbelle and I communicate it is over email and text message. Her fish skin prints are done, and she reminds me that our women play an important role in protecting and caring for our waters. That the work of coastal women maintains the earth’s balance. How fish skin practices, handed down through thousands of generations, can guide us back to our natural rhythm and to better futures. Our imagined potential.

I think of Yasbelle and that newly established thread between us, faint and draping gently across the floor. Three hundred and sixty-five days under the sun and the thread catches the light, shines a little. A glimmer of hope. We have survived the violence of colonisation. We should move beyond the tragedies of our collective present. We only need to come together, look up to the sky and imagine our hopeful futures; work together with balance and in rhythm.

[i] Eshraghi, L., & Moulton, K. (2020). ‘Kin constellations languages waters futures’, Artlink, 40(2), 6–10.

[ii] Leane, J. (2015). Historyless People. In McGrath, A., & Jebb, M. (Eds.), Long History, Deep Time: Deepening Histories of Place (pp. 151-162). Australian National University Press.

[iii] Flynn, E. (2016, November 29). In the face of a hostile dominant culture we will continue to share our art, and it will be deadly. The Guardian Australia. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2016/nov/29/in-the-face-of-a-hostile-dominant-culture-we-will-continue-to-share-our-art-and-it-will-be-deadly

[iv] Justice, D. H. (2018). Why Indigenous literatures matter. Wilfrid Laurier University Press.

—

Eugenia Flynn

Eugenia Flynn is a writer, arts worker and community organiser. Eugenia’s thoughts on the politics of race, gender and culture have been published widely. She identifies as Aboriginal, Chinese Malaysian and Muslim, working within her multiple communities to create change through art, literature and community development.

Yasbelle Kerkow

Yasbelle Kerkow is an Australian-born, Fijian (vasu Batiki, Lomaiviti) artist. Her work focuses on promoting Pacific communities in Australia and communicating Pacific stories through the arts. Her practice centres on weaving, using pandanus, flax, coconut fibre, cotton core and fabrics. Yasbelle is a community arts facilitator and leader of the Kulin Nations (Melbourne) based art collective New Wayfinders.

—

Join the PCA and become a member. You’ll get the fine-art quarterly print magazine Imprint, free promotion of your exhibitions, discounts on art materials and a range of other exclusive benefits.