Still in my Mind

Curator Brenda L. Croft discusses the exhibition Still in my Mind at Charles Darwin University Art Gallery.

21 January, 2019

In Exhibitions,

Printmaking, Q&A

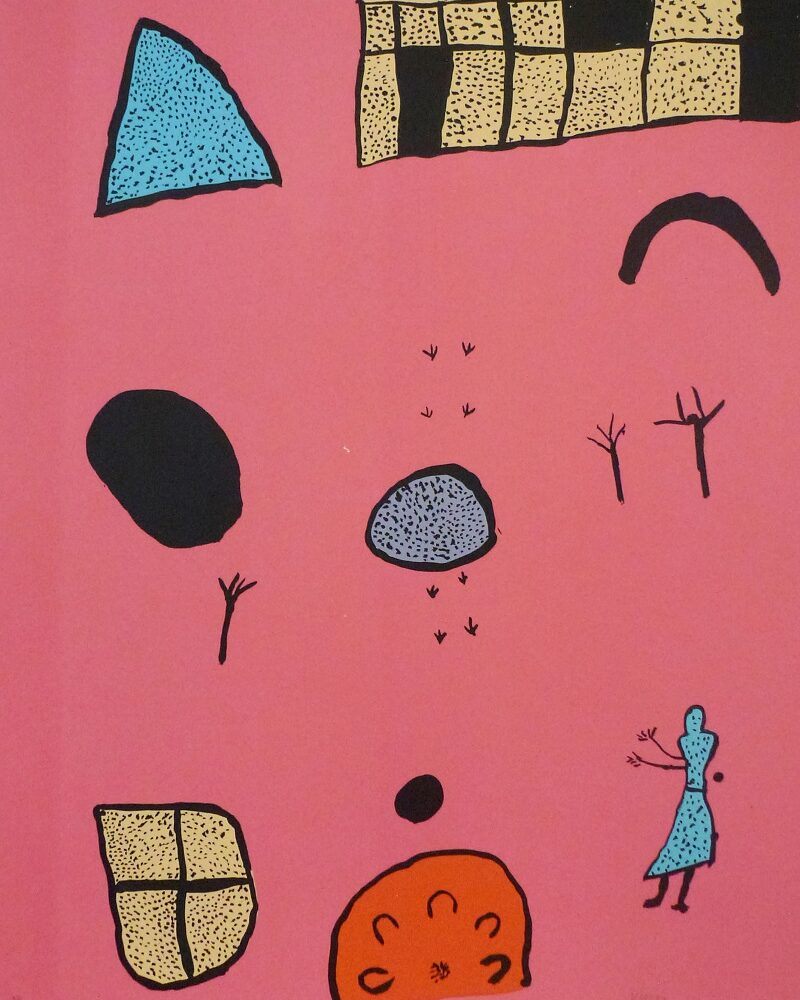

From top: Violet Wadrill Nanaku, Humpy House, Jinparrak, 2013, screenprint on BFK Rives paper, 76 x 56cm. Courtesy the artists and Karungkarni Art and Culture Aboriginal Corporation.

Brenda L. Croft, Self-portrait on country, Wave Hill, 2014, 2014, detail from Self-portraits on country, Wave Hill, 2014, installation, pigment print on archival paper, 42 x 59.5 cm. Courtesy the artist, Stills Gallery, Sydney and Niagara Galleries, Melbourne.

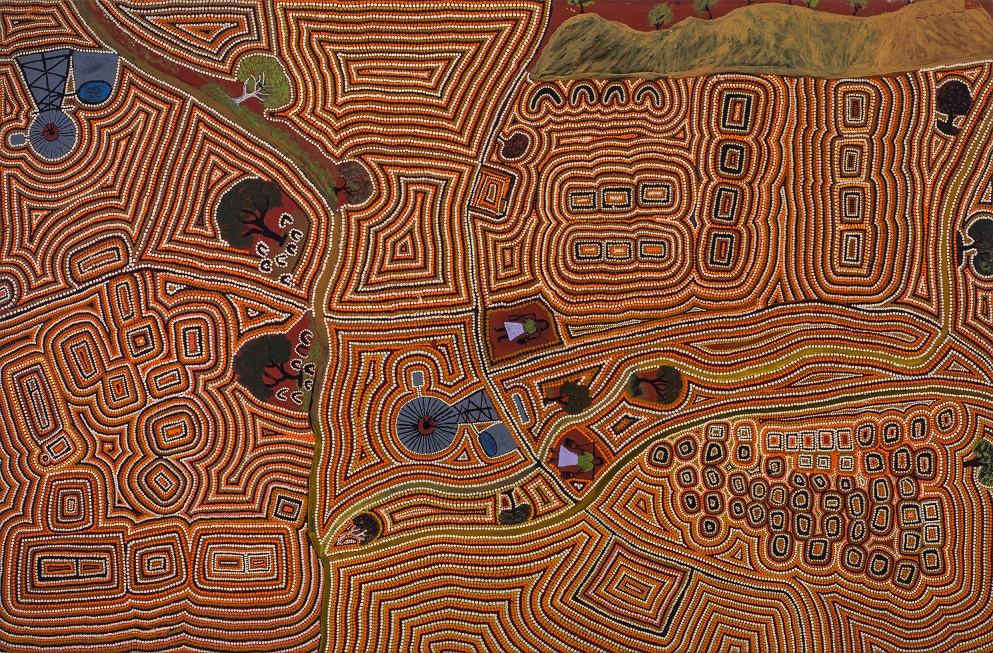

Biddy Wavehill Yamawurr Nangala and Jimmy Wavehill Ngawanyja Japalyi, Jinparrak (Old Wave Hill Station), 2015, synthetic of polymer paint on canvas, 150 x 96cm. Courtesy the artists and Karungkarni Art and Culture Aboriginal Corporation.

Dr Hannah Middleton, Vincent Lingiari with Gurindji Mining Lease and Cattle Station sign, 1970. Courtesy of Dr Hannah Middleton.

Curator Brenda L. Croft discusses the exhibition Still in my Mind at Charles Darwin University Art Gallery.

–

Imprint: The 1966 Wave Hill Walk-Off is at the centre of the exhibition – can you describe the nature of this event, its significance, and your connection to it?

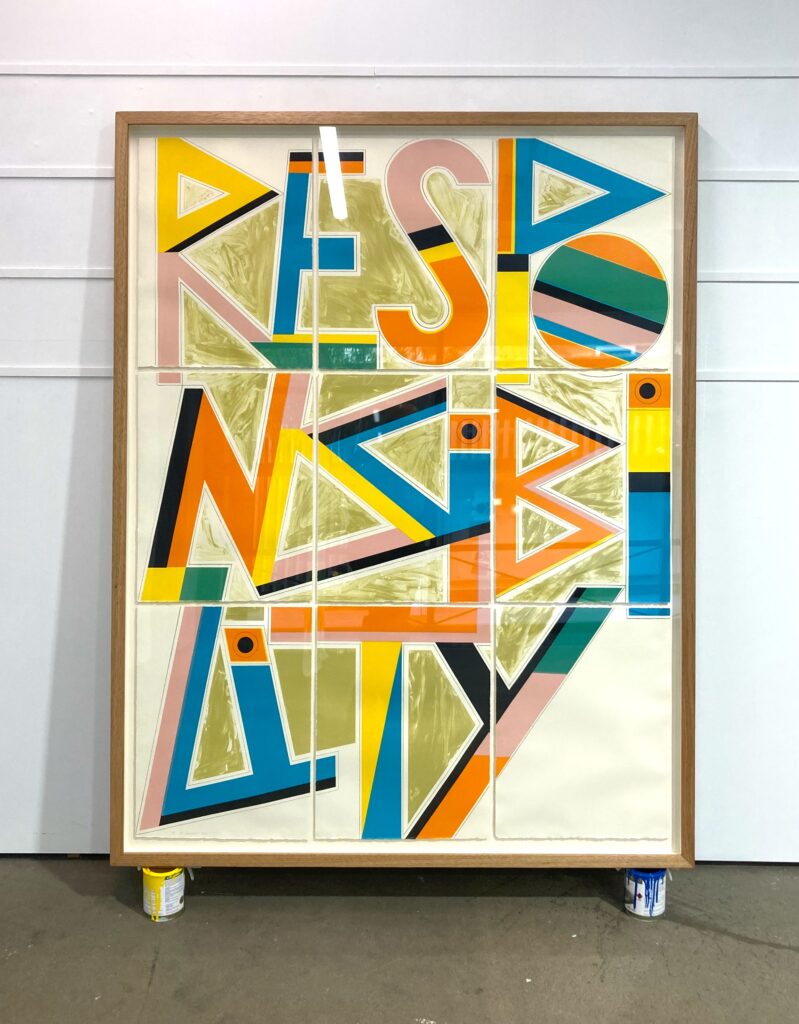

Still in my mind: Gurindji location, experience and visuality is inspired by the words of revered Indigenous leader Vincent Lingiari, ‘that land … I still got it on my mind’, this exhibition reflects on the Gurindji Walk-Off, a seminal event in Australian history that reverberates today. The Walk-Off, a nine-year act of self-determination that began in 1966 and sparked the national land rights movement, was led by Lingiari and countrymen and women working at Wave Hill Station (Jinparrak) in the Northern Territory.

However, while the Gurindji Walk-Off from Wave Hill Station on 23 August 1966 is a key story in the exhibition, it is part of a much larger story/ies, which are represented and expressed through diverse media and contexts.

I am connected to Gurindji/Malgnin/Mudburra peoples through my father Joseph’s side. He was born on Victoria River Downs c. 1926. He and my grandmother, Bessie, were taken to Kahlin Aboriginal Compound in 1927 and from there he was removed from her care in 1930 and taken to Pine Creek Boys Home, then to the Bungalow/Half-Caste Children’s Home in 1931.

My father lost contact with my grandmother in the early 1940s when women and children were evacuated from Darwin, following the Japanese Air force’s bombing of the city and he thought she had died. It was not until 1968 he learnt she was alive through correspondence with the NT Chief Protector of Aborigines. In 1974 our family travelled to Darwin to be reunited with her shortly before her death later that year.

My father always knew he was Gurindji/Mudburra and my brothers and I were brought up with a strong sense of pride in our Indigenous heritage, instilled by both parents. We discovered our other cultural connections after returning to country. The Gurindji Walk-Off from Wave Hill was an event of great pride for our family.

In 1989 my father travelled back to Victoria River country for the first time since he was taken to Darwin six decades earlier. I followed in his footsteps in 1991. After his death in 1996 my brother Timothy and I took our father’s ashes home and following a memorial service at Kalkaringi he was buried on 22 August, the day before the 30th anniversary of the Walk-Off.

Since that time I have returned regularly to our father’s country. Still in my mind: Gurindji location, experience and visuality developed from these ongoing journeys to our traditional homelands and also visiting displaced family and community members, all of which has been integral to my practice-led research project.

Imprint: How did you come to see the Walk-Off as a potential springboard for an art exhibition?

I was intrigued that the Walk-Off, while considered as part of Australian society’s national history (it is featured on the National Museum of Australia’s 100 Defining Moments of national history website), the exhibition encompasses stories and archival dating back to pre-contact with kardiya and through to 21st century experience. One of the major outcomes of my practice-led research entailed walking the Wave Hill Walk-Off Track. It was a humbling, stumbling (literally and metaphorically) experience to walk the actual track, which I did over a number of years, with and without family and community members who acted as guides.

Initially family members led the way and then I would return solo and take further photographs, record audio and video. I often retraced sections of the track as well. These components were conducted during different seasons and at different times of the day.

I found it incredibly moving retracing the steps of those 200+ activists over 4 decades after they did. I walked the Track as a tribute to those people, but also in homage to those who were taken from our community and never made it home (my paternal grandmother, uncles, aunts, cousins, brother), and also for those who will travel the Track in the future. It was never simply about walking 22 kilometres of country, it was also about walking through and across temporal space and place.

There are extensive interviews with and videos of community members at Kalkaringi, Daguragu, further afield in the Victoria River region, and in Darwin, who address what it means to be Gurindji, in all their diversity.

Imprint: Can you describe some of the works in the show and what visitors are likely to experience at the exhibition?

From walking the Wave Hill Walk-Off Track, and other sites associated with Gurindji community members who were removed from their homelands, I created an experimental, immersive, large-scale audio-visual work, ‘Retrac(k)ing country and (s)kin’, which incorporated material recorded over a number of years, alongside archival audio and video footage from other sites relevant to my father and immediate family’s journey as members of the Stolen Generations; my late brother Lindsay’s research with my father conducted in 1989; and my father’s own research on his life story. A multi-faceted, multi-layered work it is intended as a metaphorical heartbeat for the entire exhibition, drawing together elements from Victoria River country and people and displaced Gurindji community.

Dr Felicity Meakins: The Gurindji language plays an integral role in the exhibition. Many of the paintings by artists from Karungkarni Art and Culture Aboriginal Corporation were originally produced for Yijarni: True Stories from Gurindji Country which is a collection of oral histories told by Gurindji elders in their own language. A number of these stories had been told previously to historians and anthropologists in their best English but with not nearly the same detail, humour and pathos as the stories from Yijarni, which are told in their first language, Gurindji.

The artworks were created during a Karungkarni Arts artist camp in 2015, facilitated by Penny Smith (Karungkarni Arts manager), Brenda and Felicity, and supported by the Murnkurrumurnkurru rangers. Artists listened to the recorded stories from Yijarni and produced beautiful visual interpretations of these stories over a number of days camped at Warrijkuny on Gurindji country.

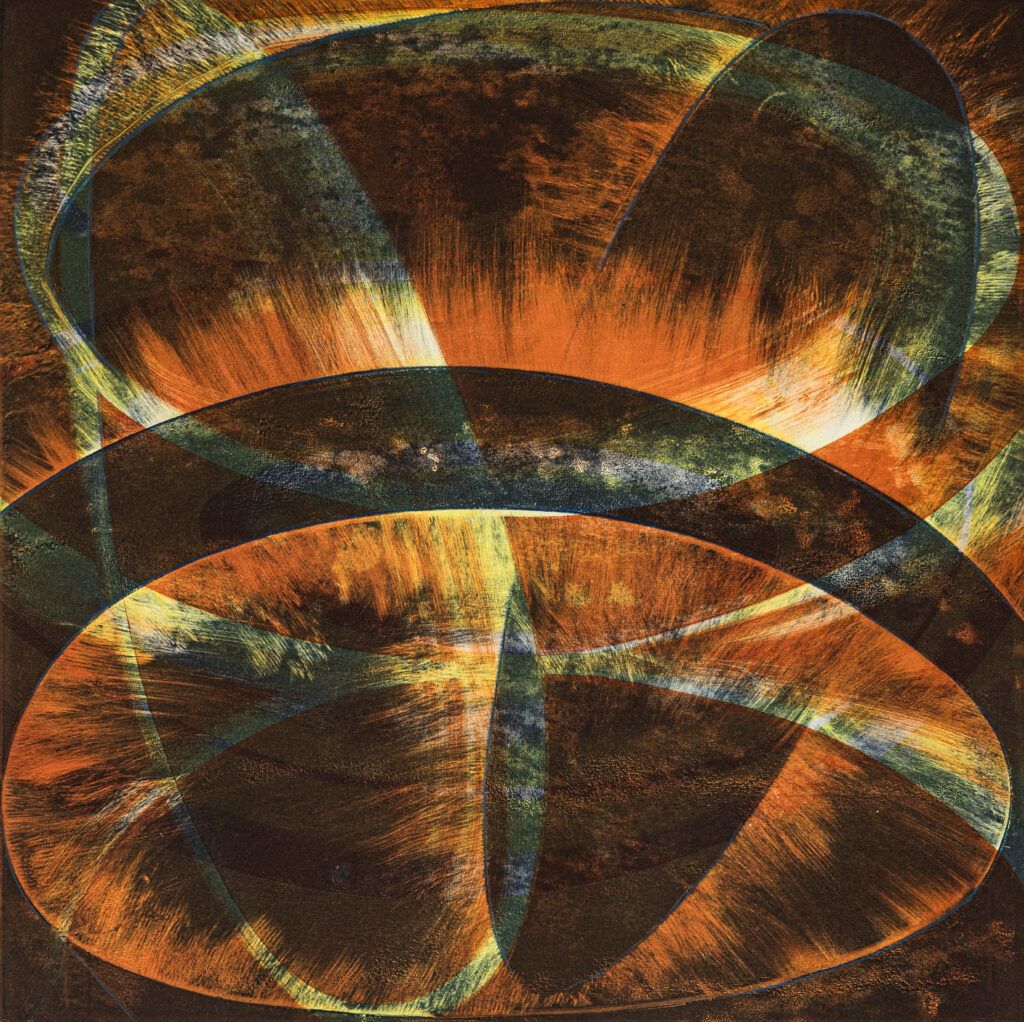

Other works included prints by Karungkarni artists created during a cultural exchange between Karungkarni and Megalo Print Studio as part of Canberra’s 2013 Centenary celebrations; prints created by Brenda L Croft during the Indigenous Summer School at Cicada Print Studio, UNSW Art & Design, 2015; extensive photographic, audio, and audio-visual archives spanning the 1920s – 1970s; photo-media; found objects from Jinparrak (Old Wave Hill Station); repatriated objects and textiles.

Imprint: What were some of the challenges involved in curating this show?

Still in my mind: Gurindji location, experience and visuality is a model for representing diverse, specific Gurindji histories, and the contemporary experiences of culturally affiliated Gurindji people – whether we are living on customary homelands or are part of a broader displaced community.

This project could only be undertaken as a collaboration, not only with family and community members, but also with other colleagues, such as Dr Felicity Meakins, whose Gurindji language projects, facilitated through UQ and Karungkarni Art and Culture Aboriginal Corporation, Kalkaringi, have been conducted for many years, resulting in publications such as Yijarni: true stories from Gurindji country (2016) and Wajarra: Songs from the Stations (2018).

–

Still in my Mind is at Charles Dawrin University Art Gallery until 16 February.