From top:

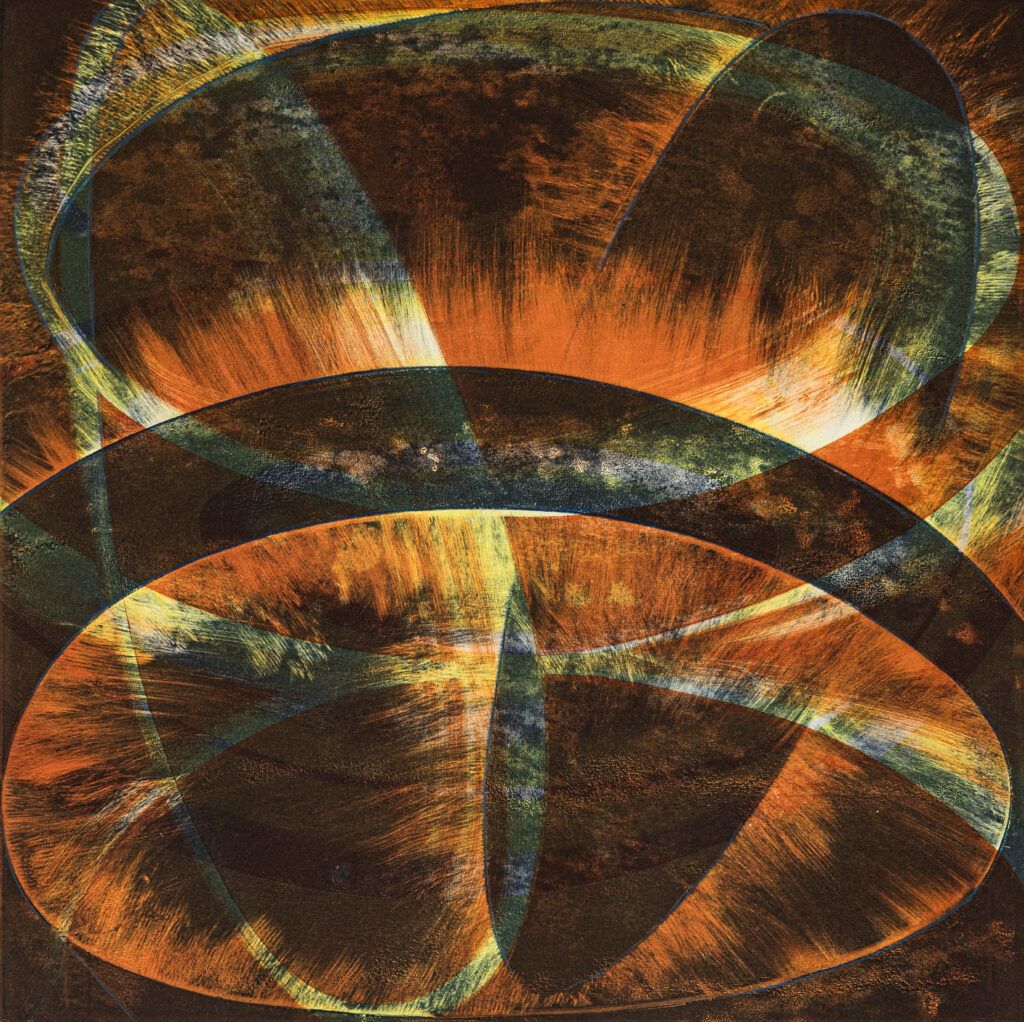

Petr Herel, Pomme Noire, 1970, etching, edition 30, 63.8 x 49.7 cm

Petr Herel, c.1980.

Remembering Petr Herel.

I first met Petr in 1974 when I was asked to write about his prints for Imprint, the Print Council of Australia’s Quarterly journal. Recently returned from almost 3 years of living in London and travelling in Europe absorbing a world of art that never quite made it into the art history with which I had grown up and studied – and in the process of shifting my focus from printmaking to post graduate studies in Art History, the discovery of Petr’s extraordinary etchings and engravings were a gift that propelled my understanding way out of my comfort zone. It was to be the beginning of an enduring and enriching friendship – and for me the beginning of writing about art.

Just over a week ago, I stood by the bedside in St Vincent’s Hospital where a few hours earlier our treasured friend, Petr Herel, had departed this life – and for the next two to three hours tried to draw his countenance in death. I regret to say that his altered likeness eluded me.

A week later, struggling to write about this remarkable and charming man, I fear he still eludes me. It is of small comfort, but my sense of Petr’s elusiveness, has been echoed by others who knew him – though as one mutual friend observed, that was part of his charm. Paul Uhlmann, who will speak of the gift and legacy of Petr as a loved and legendary teacher, observed in a message to me that “he was complex – and a great deal was left unsaid”. And – I’m quite sure – that was not a product of English being his fourth language, learned when he was in his thirties. He was highly articulate – and elusive!

Since the death of his beloved wife almost 6 years ago, the talented and spirited Dorothy Herel, one has been inclined to describe Petr as melancholy – and though her loss rendered this condition profound, he was no stranger to that attribute… a propensity which I have little doubt was freighted in the loss of his homeland, his mother tongue and the rich European culture which was his intellectual and artist inheritance and of which I will speak a little more.

Chiding him one day when I found him in a particularly morose state, I suggested he look not only at what he’d lost but what he still had: his daughters and his grandchildren whom he adored – and what he’s achieved. He looked at me mournfully, shaking his head, and said “It’s no use – we Slavs are all like this!” I must report that he cheered up dramatically when Sam, his grandson, came to dwell in Greeves Street early in the Pandemic, and to whom, to my amazement, he happily surrendered his studio room.

But he was equally capable of mirth and laughter and – as another friend commented – “he delighted in people who did not take themselves too seriously”. His mischievous sense of humour was always evident, though rarely without irony and occasionally tinged with something sardonic. A perfect example of this, is his naming of his second artist’s book press the Uncollected Works Press. And of course, if one thinks about it, the name of his first artist’s books press, co-founded in 1980 with his closest friend and artistic collaborator, Thierry Bouchard, namely, the Labyrinth Press is equally droll – perhaps especially to those who know their Greek Legends.

It is of note that he rarely talked about himself; the Self he most readily shared was that which was manifest in his art. It was rare to visit the Herel household and not spend time looking at the latest drawings or slowly turning the pages of an exquisite artist’s book with its engrossing, fantastical images set in opposition to the spare, elegant pages of typography, the darkly inventive and playful meanings and metaphors of Petr’s imagery slowly revealing themselves…. harbingers of mortality, of human folly and desire. But I guess that most of us here today have been privileged participants in this gentle ritual – what one friend, the distinguished art historian and curator, Anna Gray, described as Petr’s conjuring of “visual magic”.

While it is my task to honour Petr’s lifetime of distinguished and exceptional achievement as an artist, before I give up on my tentative attempts to conjure this modest, brilliant and evasive man, may I share this lovely insight into Petr’s character by his astute granddaughter, the now seven-year-old Jana, who has spent this past 15 months of endless lockdowns, living in Greeves Street with her parents, Sophie and Markus, her cousin Sam and grandfather – known by the Czech word for grandfather, Deda.

When told of her beloved Deda’s death by her father, discussion followed about what happens to someone after their death. Markus recounted some of the beliefs held about the fate of our immortal souls, including that of reincarnation. “So, what creature do you think your Deda would come back as?”, he asked little Jana. After the briefest consideration, Jana pronounced “Deda would come back as a bird”.

It seemed to me that Jana had nailed it….and I note in writing this, that each time I think I’ve got close, he flies away.

Perhaps he has always been a bird? He could fly where we mortals were earth bound, and like a bird, was equally elusive. It is as though he dwelt in another world – an inner world which is embodied only in that “visual magic’ which is his art.

Of course, the image of a bird is something of a leitmotif in his work – a symbol of transience, of flight, of freedom but also of life’s brevity – and of the soul departing the body. In Petr’s art, the bird is sometimes a creature who loaned its wings to angels but who might equally eviscerate its prey. Many of you will be the recipients of small cards or notes from Petr on which a bird is drawn. When I told Jana’s pronouncement to my friend, the maverick curator, Ted Gott, he agreed and added “I see him as a Hummingbird, hovering with burin over a copper plate”. Perhaps it is worth noting here, that the title of one of his miraculous artist’s books is Four pages from a Register of Souls…

In his migratory travels, in 1973, he alighted in this barely civilized country, whose language he hardly spoke and where his transcendent, metamorphosing and often dystopian imagery was alien. So it is not difficult to countenance his melancholy.

He was born in 1943, in the ancient town of Hořice in the north of Bohemia and grew up in verdant countryside immortalized by Dvorak’s music. And then, from the age of 14, after winning a coveted scholarship to the Prague College of the Visual Arts, he lived in that glorious city which had embraced Mozart and whose Gothic, Renaissance and Baroque buildings housed treasures which here we are lucky to glimpse in museums or in occasional imported exhibitions. Even under the oppressive Communist regime, which he loathed, Prague was a city rich in history and art and literature. Australia in 1973 must have seemed a wasteland.

I became acutely aware when I tried to write that first piece on his work for Imprint back in 1974, that the rich Mittel-European intellectual and artistic legacy under the Hapsburg Empire has been almost entirely excluded from our very partial and limited understanding of European history. There was almost no point of reference for his work here.

Prague was one of the principal centres of European cultural achievement in both the Renaissance and Baroque and continued to be so through the decades of the Hapsburg Empire of which it was a jewel in that Imperial Crown. And it is useful to know that Prague was also one of three great centres of the Surrealist movement in the early 20th century along with Paris and Belgium. Likewise, the literary traditions of Bohemia and her neighbours, and then his later adoption of the life, literature and art of twentieth century France where he went to live in his mid-twenties, are vital in understanding the sources of Petr’s art. His imagery’s entirely idiosyncratic and seductive elements embracing the gothic and surreal, the abstract and the figurative, the erotic and the playful, the macabre and the haunted, are the product of his intellectual and cultural inheritance.

After completing his graduate studies in graphic and book arts at the Prague Academy of Applied Arts, in 1970 – a six-year course he completed in just five – he was awarded a prize for the year’s most beautiful book produced in Czechoslovakia in that year. This led to a scholarship to work and study at the Atelier Nourrison in Paris. It was the beginning of another life.

There were perhaps two people central to Petr’s life – his soulmates as it were. One was his wife, Dorothy, the lodestar of his life, whom he had met in Paris in 1970, married in 1972, and with whom he had two daughters, Sophie and Emilie. Their lingua franca was and remained French – a fact which has some bearing on his personality and on the evolution of his art. Petr and Dorothy came to Australia in 1973 when the Communist Government of Czechoslovakia would not allow Dorothy to live with him in Prague without renouncing her Australian Citizenship. Dorothy was the driving force in his life, practical, and responsive to Petr’s vocation, organizing their quotidian needs, freeing him to create his “visual magic”, to which she was his essential witness.

The other person central to Petr was the Frenchman, Thierry Bouchard, Poet, Printer, Typographer extraordinaire, Editor and alchemist in the world of artist’s books – and Petr’s spiritual and artist kin. Petr and Thierry became friends when the Herels returned to France in 1976 and lived in Beaune, near Dijon where Petr had found a teaching position in l’École Nationale des Beaux Arts de Dijon and where Thierry was teaching Typography. Though Petr and Dorothy and their little girls were unable to settle permanently in France, a partnership had begun.

Back in Australia late in 1978, Petr was offered work by visionary German Artist/Educator, the late Udo Sellbach who had recently been appointed Head of the Canberra School of Art. Alert to both Petr’s exceptional achievement as a printmaker and to the creative richness offered in the production of the livre d’artiste, he appointed Petr to establish a Department and Workshop in the Art School (now part of the ANU) for the teaching of artists’ books. It was life changing for Petr and his young family, and for the generations of students who studied in Petr’s wonderfully named ‘Department of Graphic Investigation’ – about which Paul Uhlmann with shortly speak.

With Thierry, Petr created the Labyrinth Press in 1980, Petr working in Canberra at the Canberra School of Art and Thierry in St Jean de Losne, near Dijon, choosing texts together, Petr working on the plates of images to be printed and sent to France and Thierry the typography and design. Until Thierry’s death in 2008, together they created a body of twenty-one livres d’artiste (artists’ books) for which they were honoured in France, and which the State Library of Victoria (through the vision of Des Cowley) and the National Library in Canberra have collected.

These limited-edition publications are a collaborative endeavour unlike any other. Artists’ books bring together poetry, printmaking, typography and papermaking, that together – in this constellation of ideas and imagery and sensitive artisanal skills – create an object, the livre d’artiste, that is a marriage of the visual and the literary and whose intimacy invites, intensifies and transforms our experience of both.

At Thierry’s death in 2008, Petr was working on a book titled titled Séquelle, which was awarded the coveted Jean Lurçat Prize in France in 2009. Later that year he was made Chevalier of Ordre des Arts et des Lettres by the French Government. Though entirely unexpected, it was a moment of recognition which affected both Petr and Dorothy deeply.

There is much more to say about Petr’s art and his legacy, but I will end with Petr’s own words about his art, recorded for an exhibition in 2010 “Working, I begin to feel an inner smile – and then I know, in that quiet timelessness, that my work propitiates the solitary soul.”

His exquisite body of work, of drawings, etchings, engravings, aquatints and artists’ books is indeed a gift to our souls, both solitary and collective. In that he has achieved an immortality and we are its beneficiaries. It is up to us now to ensure that his life’s work is dispersed to such institutions that will preserve it for the pleasure and revelation of future generations. A light has gone out of this world, but not out of our lives.

Elizabeth Cross, 10 April, 2022

—

Join the PCA and become a member. You’ll get the fine-art quarterly print magazine Imprint, free promotion of your exhibitions, discounts on art materials and a range of other exclusive benefits.