From top:

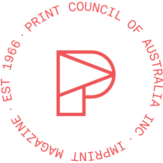

Sally Beech, Willow Court, Clapping Girl, 2021, Lino cut and embossing

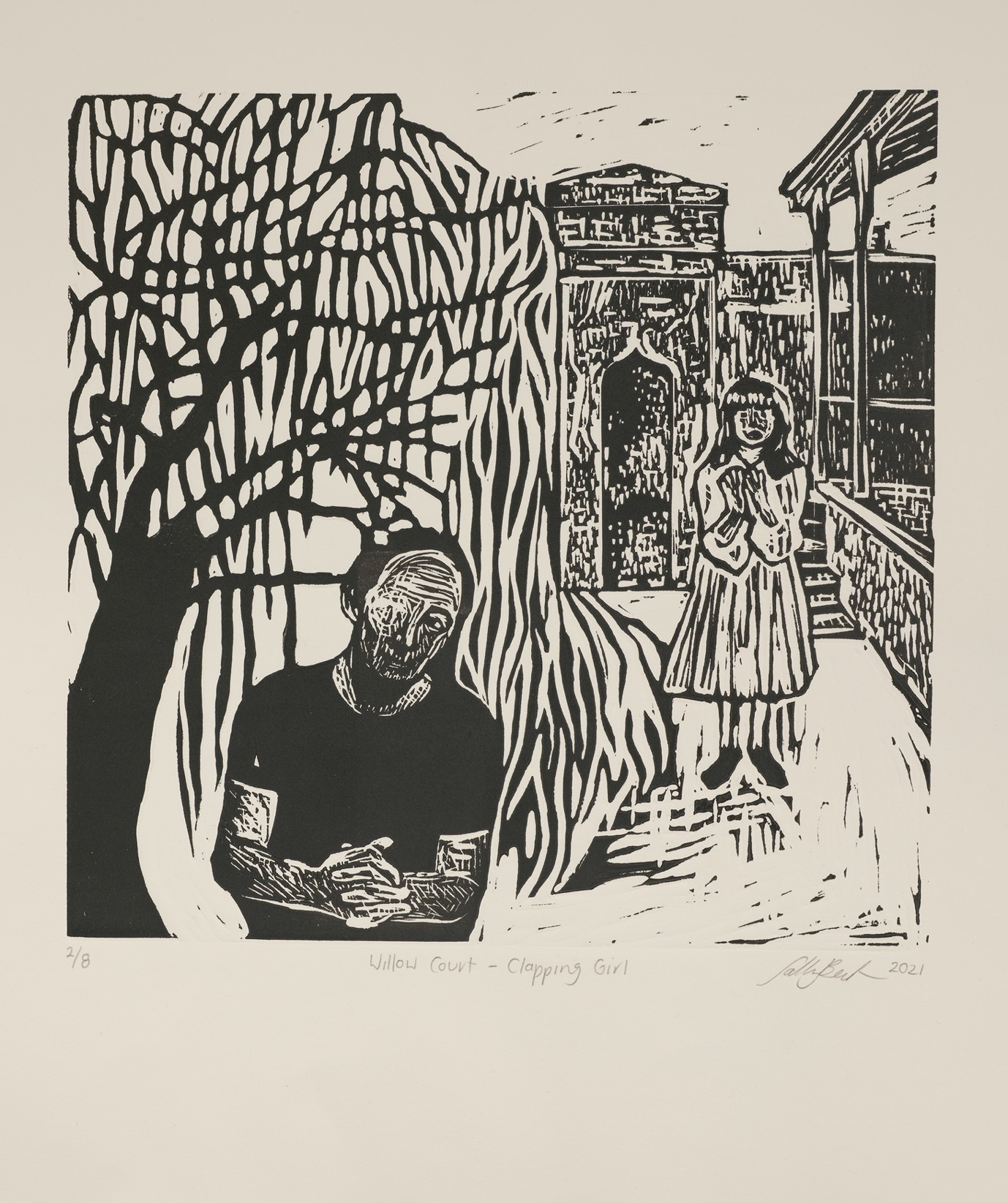

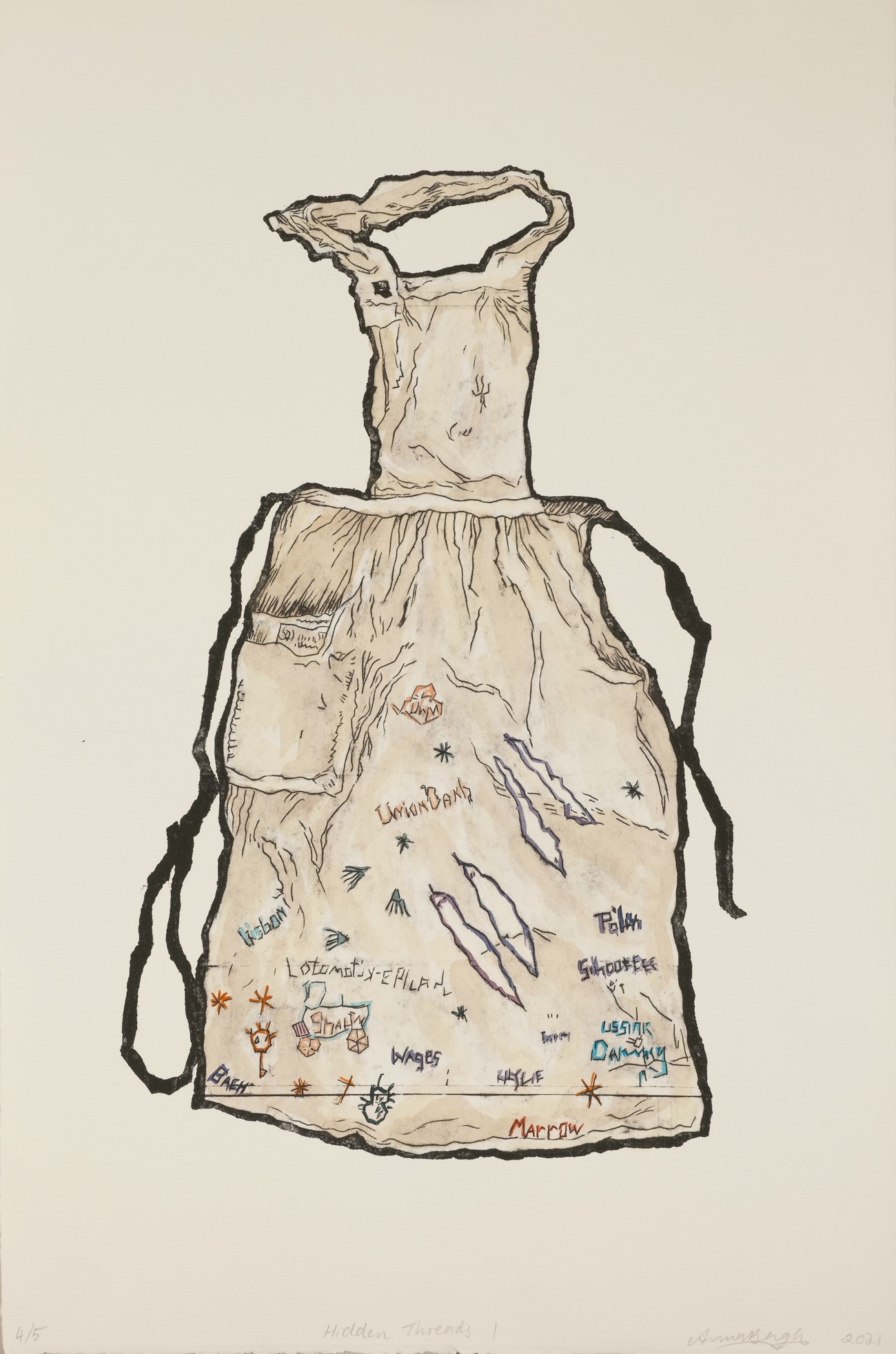

Anne Berger, Hidden Threads I, 2021, Hand coloured collograph

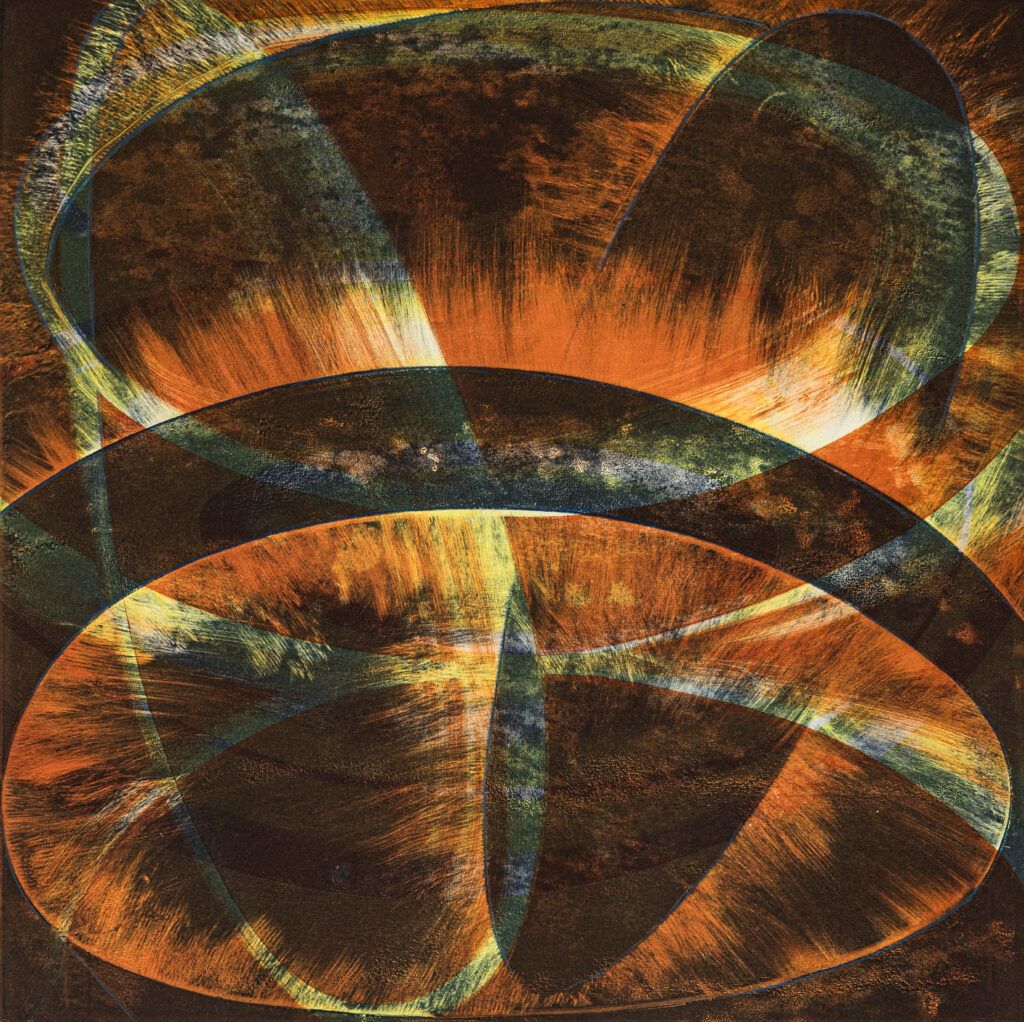

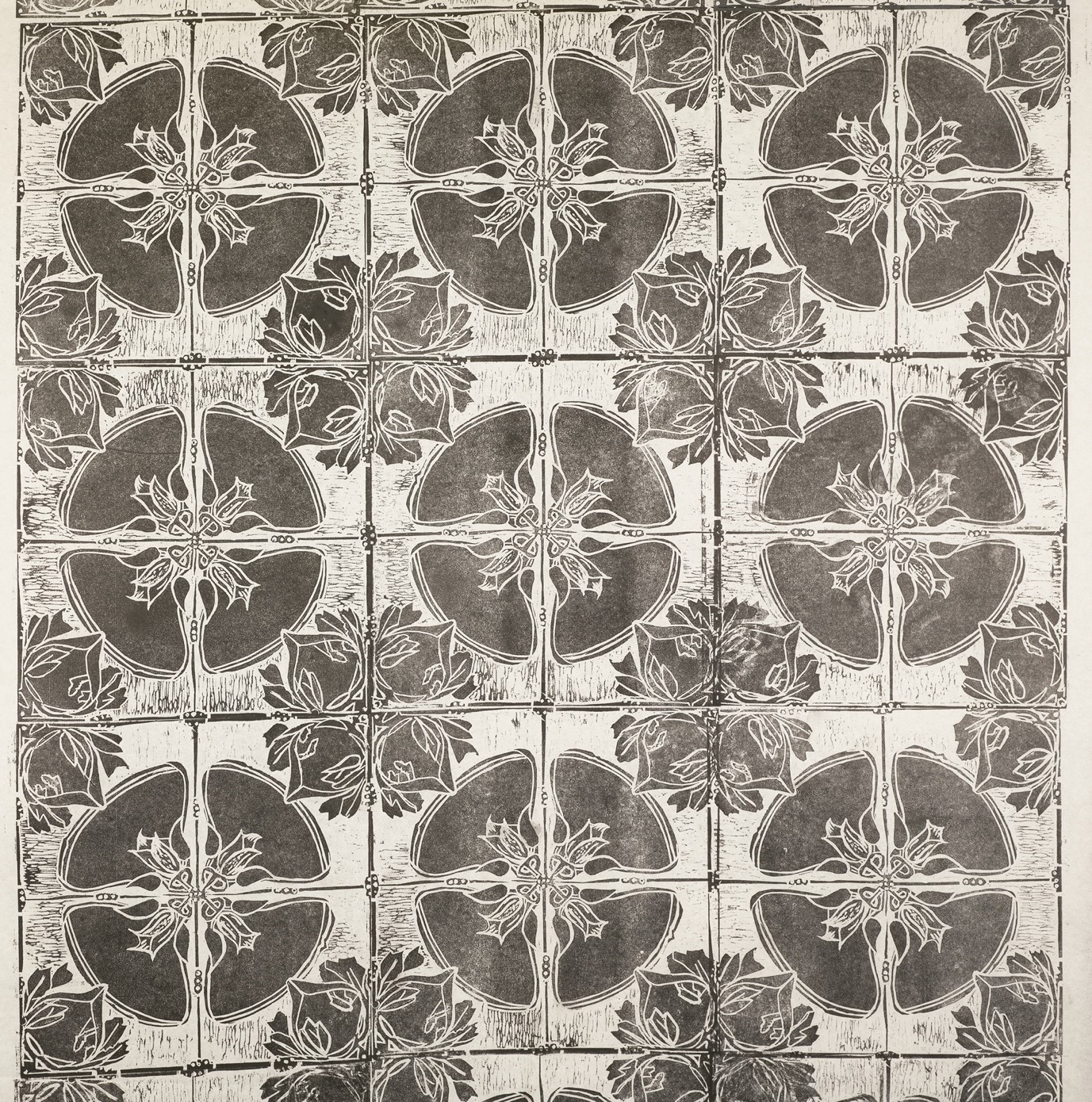

Sarah Robert-Tissot, Lotus On a roll, 2021, Hand printed linocut on Whenzho paper

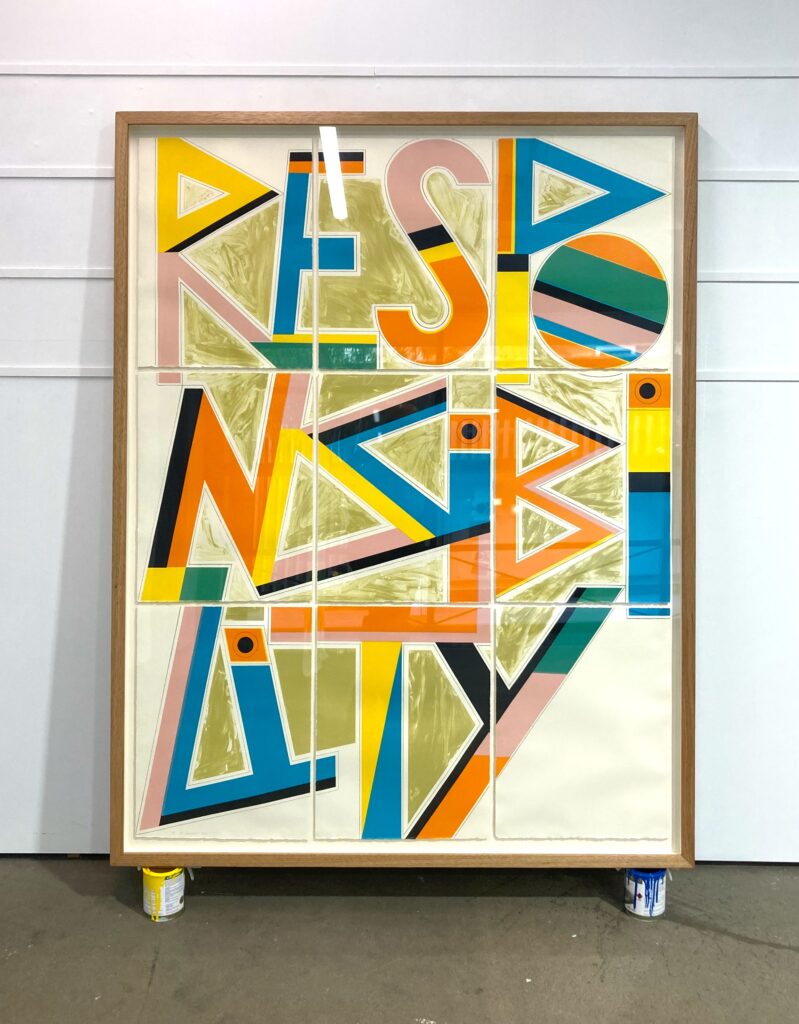

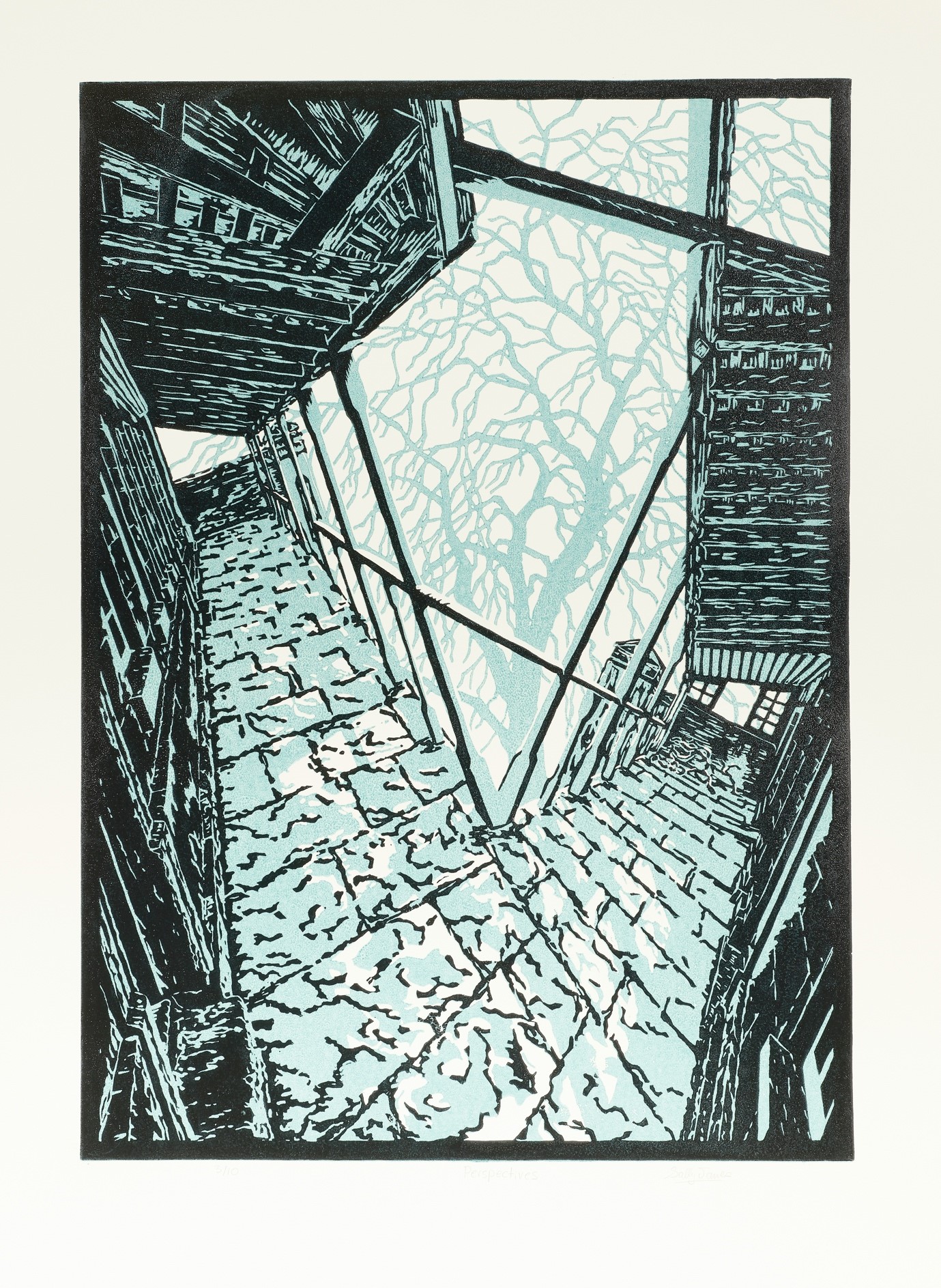

Sally James, Perspectives, 2021 Linocut

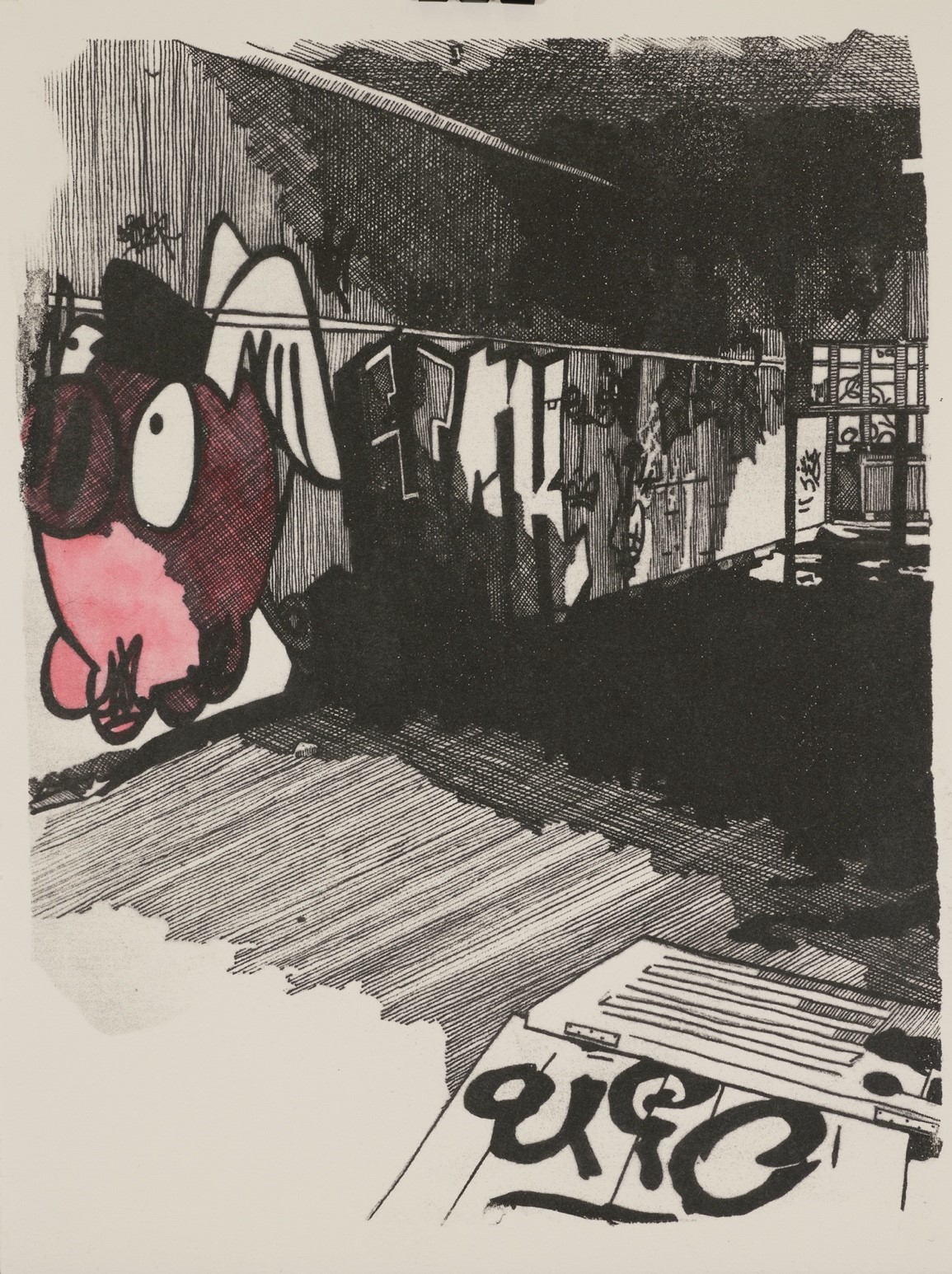

Amy Hobden, Pigs Fly and Privacy Hand coloured lithograph

New Norfolk in lutruwita, Tasmania is currently undergoing an arts and agrarian led regeneration. The town has long carried the stigma of housing Tasmania’s largest mental institution. Although closed over twenty years ago the buildings of Willow Court have stood abandoned. Artists, sensitive to the need for remediation, have used the buildings for installations, festivals and performances allowing the history of the site to resonate. Recently the Derwent Visual Arts association have taken on the care and maintenance of the buildings and have set up an ambitious program of community and contemporary art exhibitions.

Hunter Island Press, a Hobart-based printmaking organisation, was one of the first community groups to set up a project. The outcomes are exhibited in Frame of Mind, held in the Barracks galleries at Willow Court. The walls are permeable, the wood and paint scarred with stories, corroborating the presence and now absence of many people in what was once a bustling institution. Meeting with the historical friends of Willow Court the artists began to their research into the history and the stories of residents that are embedded in the site.

It is uncanny viewing the work in the gallery whilst the site is being repaired. This is not a preserved museum site but rather a living moment of transformation. The prints make the walls speak. As we walk through the buildings we see them reflected in prints such as Carolyn Canty’s work collaged with ghostly images of past residents. We are invited to imagine the lives of inhabitants, the moments of reprieve and the despair that accompanies mental illness. Jeanie Edwards’ The Onlooker places a figure at a window contemplating the changes to Willow Court and how we are now invited to come inside. Jonathon Burgess highlights the wobble in the glass of the old window as it has slumped with age, reflecting on his own mental health crisis and wondering whether distortion was reality or hallucination. Sally James uses multiple perspectives of staircases twisting them around the central image of the willow tree, providing both a reflection on the state of some of the buildings with stairs leading to nowhere whilst revealing the quandary of making sense of multiple histories.

Images of the architectural buildings from historical documents and on-site observations haunt many of the works. John Ingleton uses historical documents and willow leaves to reference the colonial period whilst adding emojis of how the occupants may have felt. Janice Luckman has the Willow Court building as a backdrop to a baby in a pram, a reference to a more personal association as she discovered that her cousin Jennifer spent her short life there due to the care required for her congenital condition. Maggie Aird remembers the numbers man whose mathematical calculations are scratched into a wall. Insane or a genius, the possible realities of the inmates are destabilising thoughts.

The plight of women is a recurring theme. Rob McKenna considers the trauma of forced migration from the potato famine in Ireland. Connecting the story of his ancestors with the conditions that may lead to becoming inmates of a mental institution. Patricia Martin reveals the women in moments of despair but also in times of camaraderie and companionship that occurred within institutions. Linda Pollard considers the site as ‘home’ for the children and the conflicting tales of joy and hardship held within the historical records. Wendy McGrath uses native grasses of the area and dark brooding negative spaces as she empathises with the unsettling states of the institutionalised. Moments of reprieve and individuality are shown in Anna Berger’s Apron series based on the discovery of a secret stash of aprons securely hidden in the building. Craft work within the building was used as a springboard to develop skills in cutting but became a provider for printing extension. The work of Sarah Robert-Tissot used the beautifully crafted pressed tin ceiling work to extend her linocutting and printing skills into a large ambitious work.

Many artists have captured the transitional state of the buildings with remains of furniture and degradation apparent from years of neglect. Amy Hobden documented the recent state of the buildings with her compositions of graffitied walls whilst Tersia Oosthuizen uses collagraph to evoke dried branches and detritus against a wall to speak of the tangled memories that haunt the place. Rowena Bond leads us up narrow stairwells to sparce iron beds in dingy rooms whilst Alicja Boyd has caught a moment of change with items gathered up behind a doorway making way for the current gallery space. The items are gone but the door remains dilapidated.

The close observations of the textures of handmade clothes by the inmates in Tina Curtis’ monoprints considers who the inmates of the hospital may have been and how they were treated under theories such as phrenology, the mapping of the skull. Cath de Little accurately describes the current state of the dispensary with its haunting labels revealing the testing and use of a wide range of medicines that would have varied results. Rachael French’s images of willow, bramble and poppy acts as a reminder of the many theories that continue to circulate around treatment of mental illness. Trees are seen as memory keepers, sentinels of the lives of the inhabitants and the associated staff in Kaye Green’s lithographs.

The project assists in the healing and reclamation of the site. The beauty of printmaking is the ability to have multiple and sometimes conflicting layers of information pressed together. The geological, geographical and psychological layers within these walls are made present helping to make peace with the past as we realise these people and these times are not so very different from us. Through this community project many tales have become unearthed and are spoken about, hopefully assisting in healing, and acknowledging a site bound with stigma.

_

Jan Hogan is Head of the Art Discipline and coordinator of the Drawing and Printmaking Studio at the School of Creative Arts, University of Tasmania.

—

Join the PCA and become a member. You’ll get the fine-art quarterly print magazine Imprint, free promotion of your exhibitions, discounts on art materials and a range of other exclusive benefits.