From top:

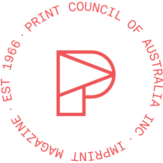

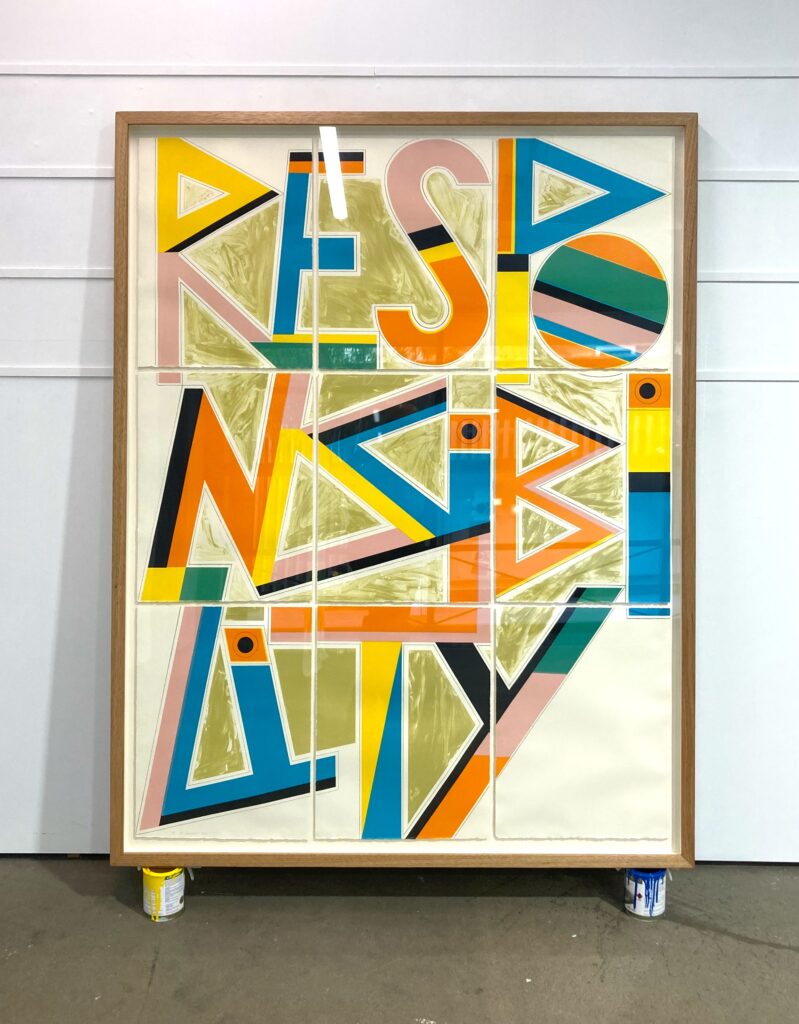

1. Jake Holmes, Writing the Climate (A), 2019, screenprint, colour inks on paper, 51 x 36 cm, copyright the artist, photograph: Flinders University Art Museum

2. Jake Holmes, 2019, Holy Rollers Studio, photograph: Brianna Speight

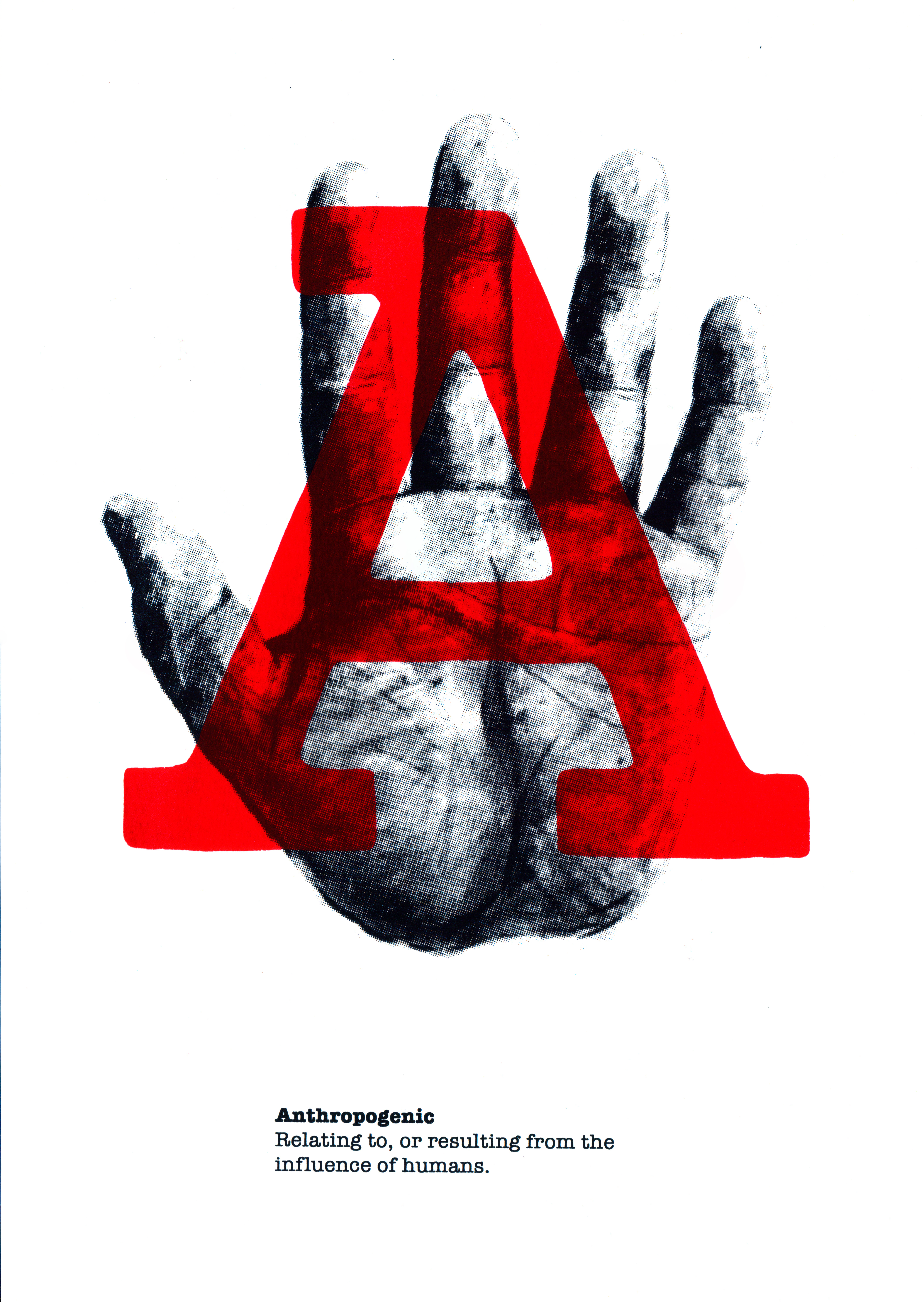

3. Jake Holmes, Writing the Climate (B), 2019, screenprint, colour inks on paper, 51 x 36 cm, copyright the artist, photograph: Flinders University Museum of Art

4. Jake Holmes, Writing the Climate (C), 2019, screenprint, colour inks on paper, 51 x 36 cm, copyright the artist, photograph: Flinders University Museum of Art

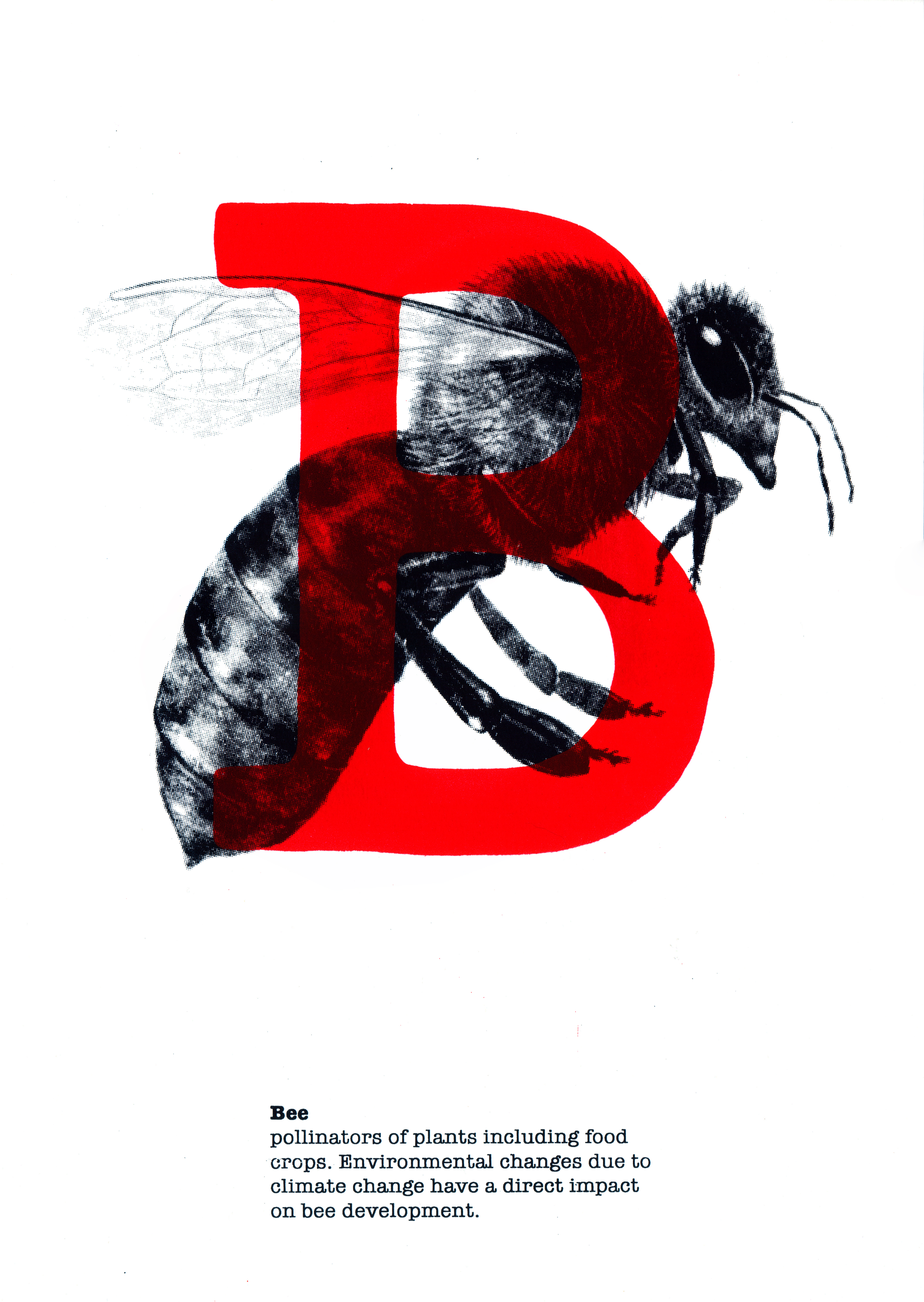

5. Jake Holmes, Writing the Climate (Otto), 2019, screenprint, colour inks on paper, 150 x 650 cm, copyright the artist, photograph: Flinders University Museum of Ar

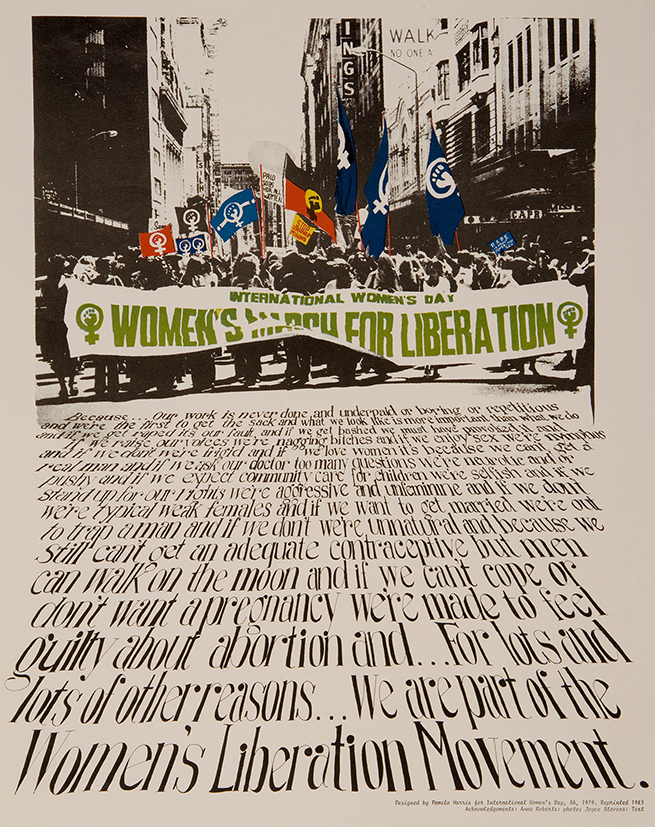

6. Pamela Harris, International Women’s Day: women’s march for liberation, 1983, screenprint, colour inks on paper, 71.2 x 50.9 cm, Gift of the Australian Experimental Art Foundation, Collection of Flinders University Museum of Art 2879.118, copyright estate of the artist

7. Helen Printer, 4 (Franklin protest), 1983, screenprint, colour inks on paper, 61.1 x 43.2 cm, Gift of the Australian Experimental Art Foundation, Collection of Flinders University Museum of Art 2879.066, copyright the artist

Over the course of Australia’s political history I can recall a few (far too few) defining moments – the iconic photo of Vincent Lingiari having his ancestral lands returned to him by Gough Whitlam; Bob Hawke’s intervention to save the Franklin River from damming, as well as offering asylum to Chinese students after the Tiananmen Square massacre; John Howard’s quick action on gun control following the horrific events at Port Arthur; and Kevin Rudd’s national apology to the Stolen Generations. Action on climate change should be counted amongst these moments, but all evidence presently points to its absence. Are we sitting on the cusp of another defining historical moment, or will the voices of younger generations continue to be ignored in favor of economic greed? These are some of the questions South Australian printmaker and political activist Jake Holmes contemplates within his latest body of work, Writing the climate.

The phrase the personal is political[1] resonates truly in Holmes creative practice. In support of Australian marriage equality he and fellow artist Peter Drew adapted the eminent cricket anthem into the iconic, rainbow C’mon Aussie C’mon poster campaign. This was a sensitive topic for Holmes and his family – at the time, his mother’s same-sex relationship was not recognised by law. Writing the climate addresses another subject close to home. Now a father, Holmes’ concerns are focused on what the state of the world will be like for his son if the Australian Government’s failure to acknowledge climate change and provide support to address it continues.

Holmes’ call to action was conceived as part of The Guildhouse Collections Project. He was awarded the unique opportunity to immerse himself in the archive of some 400 posters held in Flinders University Museum of Art’s Australian Political Print and Poster collection. Here Holmes sifted through leaves of layered colour, once destined to decorate the street and illuminate the minds of passers-by. These works now shout silently from the safety of acid-free folders and low-light conditions, waiting to be rediscovered and heard again. Holmes listened, and noticed that past environmental concerns such as water security, deforestation and nuclear power are still hotly contested topics of discussion – not to mention First Nation land rights, feminism and other issues of equality.[2] His resulting series, Writing the climate, brings 1980s environmentalism into contemporary context by highlighting the causes and effects of climate change.

Political poster artists and activists are agents of dissent; they provoke and question, and more often than not, embrace their bias[3]. Holmes does exactly this, however he endeavours to educate as well as incite. His work employs the English alphabet, and puts it to task – a system of 26 distinct characters that when combined allow us to communicate complicated ideas, in this case to unpack the complexities of climate change.

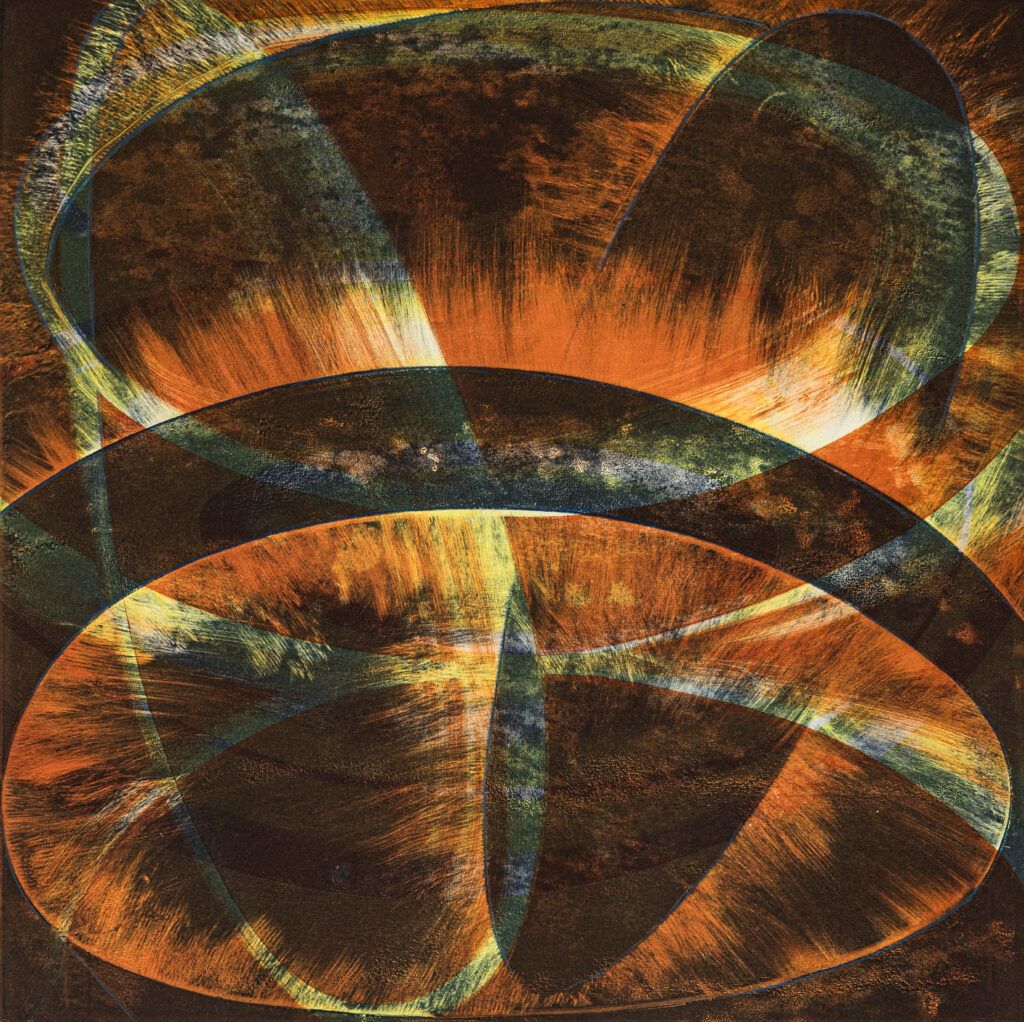

Taken by the intimacy and simplicity of Helen Printer’s gentle and meditative poster, No. 4 (Franklin protest) (1983), Holmes sought the same stillness in order to invite quiet contemplation for a lingering impact. A single layer of dusky ink distinguishes each illustration and their correlating definitions, which are then overlaid with a sheer crimson letter. The arresting palette commands our attention, like a stop sign at a busy intersection. However, the intricate detail of each individual element holds our attention, allowing us time to digest the daunting facts.

For International Youth Year 1985, Sydney-based community arts workshop Garage Graphix created a series of posters after speaking to young people about what they perceived as challenges and concerns for the world. The resulting luminous screenprints in Talking Poster Project (1985) featured direct quotes giving voice to a marginalised generation. Inspired by this project and sensing a similar situation, Holmes conducted interviews with tertiary, secondary and primary school students. He comments ‘In my opinion the voice of younger generations is frequently overlooked when it comes to issues that require large societal change. Yet these voices are currently the loudest when it comes to calling for action, as recently seen for example in the international movement of school strikes for climate change’.[4]

Suspended in Flinders University’s bustling student hub, gently stirring amongst the swirl of bodies, Holmes’ first iteration, Writing the climate (Otto), brings together individual posters to convey not just a quote but also a war cry. Secondary student Otto’s stinging barb, “No one’s gonna care about my ATAR when the planet’s dying”, captures the ‘emotional, nihilistic anxiety felt by the youth of today towards their uncertain futures’.[5] Sculptural in form, Holmes’ ambitious installation evokes the protest banner as a symbol of change and defiance. The gritty reality he presents echoes the placards held proudly by youth at Greta Thunberg’s international School Strike for Climate protests, as well as historical collection works such as Pamela Harris’ International Women’s Day: women’s march for liberation (1983).

Not all change happens on the street, but it begins there. The power of political prints and posters lies in their ability to shift from dark alleyways and sidewalks into illuminated shop fronts, homes and eventually, into humidity-controlled gallery spaces. Gradually growing in presence, they begin to permeate a wider consciousness. Their momentum and impact develops over time, but in the case of Writing the climate, expediency is critical.

The climate crisis affects everyone, but it will impact young people the most. And as Jake Holmes has emphasised in Writing the climate, we cannot speak for younger generations, instead it’s time to relinquish control, listen and support. I’ve heard whispers that the ‘kids are alright’, but the kids have got it right and they know what they want. They want to stop all new coal, oil and gas projects; they want 100% renewable energy generation and exports by 2030; and a just transition for all fossil-fuel workers and associated communities.[6] They say it takes a village to raise a child. Well, it may take a whole country of engaged, inspired youth to get the big kids in office out of their coal-filled sandpits.

Madeline Reece

Madeline Reece is a curator, writer and artist based in Adelaide, South Australia. She is currently Exhibition and Programs Assistant at Flinders University Museum of Art.

Writing the climate was at Flinders University until 30 November 2019.

[1] ‘The personal is political’ is a phrase coined and associated with second-wave feminism. It is a slogan that challenged and continues to question ‘structures of oppression’ in relation to women’s experience and inequality more broadly.

Rogan F, Budgeon S, 2018, The Personal is Political: Assessing Feminist Fundamentals in the Digital Age, Department of Social Policy, Sociology and Criminology, University of Birmingham, Birmingham, United Kingdom, viewed online 10 October 2019, <https://www.mdpi.com/socsci-07-00132.pdf>

[2] Dottore, C, 2014, Mother nature is a lesbian, exhibition catalogue, Flinders University Art Museum, Bedford Park, South Australia

[3] Wallis G J, 2013, Got the message? 50 years of political posters, Art Gallery of Ballarat, Victoria, Australia, pp.13-17

[4] Holmes J, Reece M, 2019, Writing the climate, exhibition catalogue, Flinders University Art Museum, Bedford Park, South Australia

[5] Holmes J, Reece M, 2019, Writing the climate, exhibition catalogue, Flinders University Art Museum, Bedford Park, South Australia

[6] School Strike for Climate website, viewed online 9 October 2019, <https://www.schoolstrike4climate.com/about>