From top:

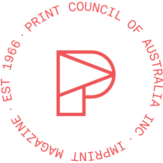

Barbara Hanrahan, Flying mother, 1976, screenprint, colour inks on paper, 59 x 48 cm, Private collection, Adelaide, © the Estate of the artist, courtesy Susan Sideris 2020

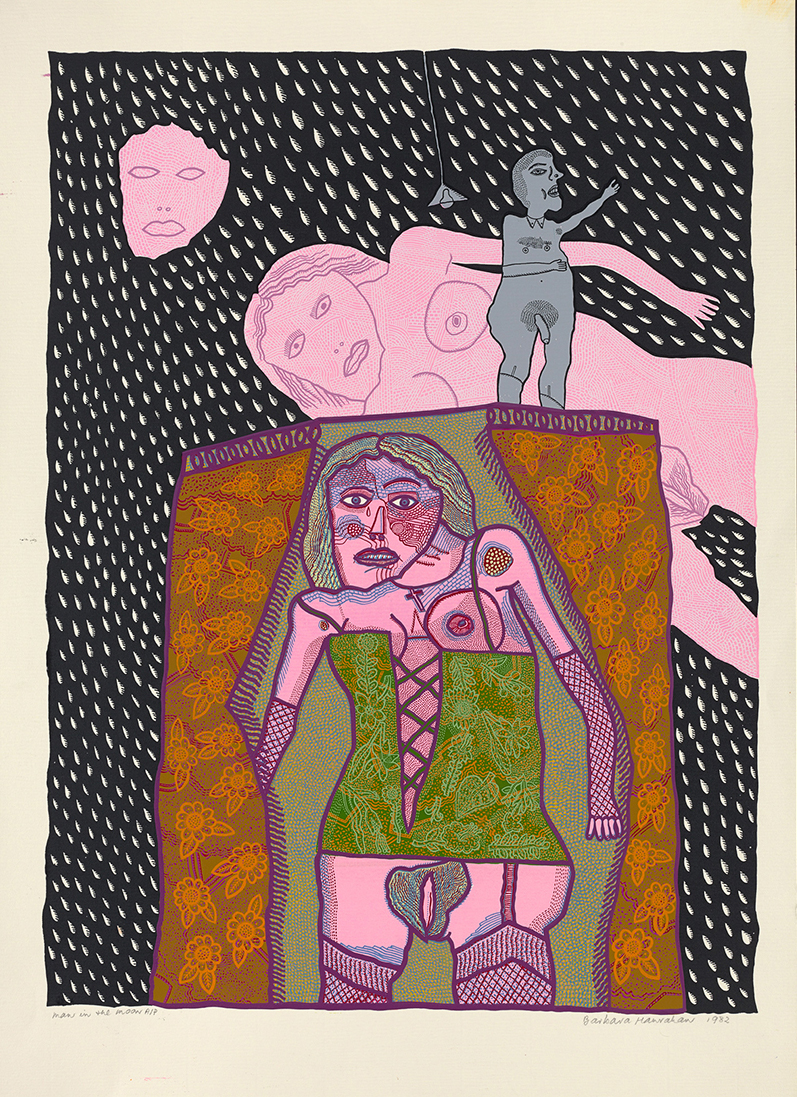

Barbara Hanrahan, Man in the Moon, 1982, screenprint, colour inks on cream paper, 70 x 52, Gift of Jonathan P Steele, Flinders University Museum of Art, Adelaide 5767, © the Estate of the artist, courtesy Susan Sideris 2020

Barbara Hanrahan, Moss-haired girl, 1977, screenprint, colour inks on paper, 63.3 x 33.1 cm, Gift of Jonathan P Steele, Flinders University Museum of Art, Adelaide 5769, © the Estate of the artist, courtesy Susan Sideris 2020

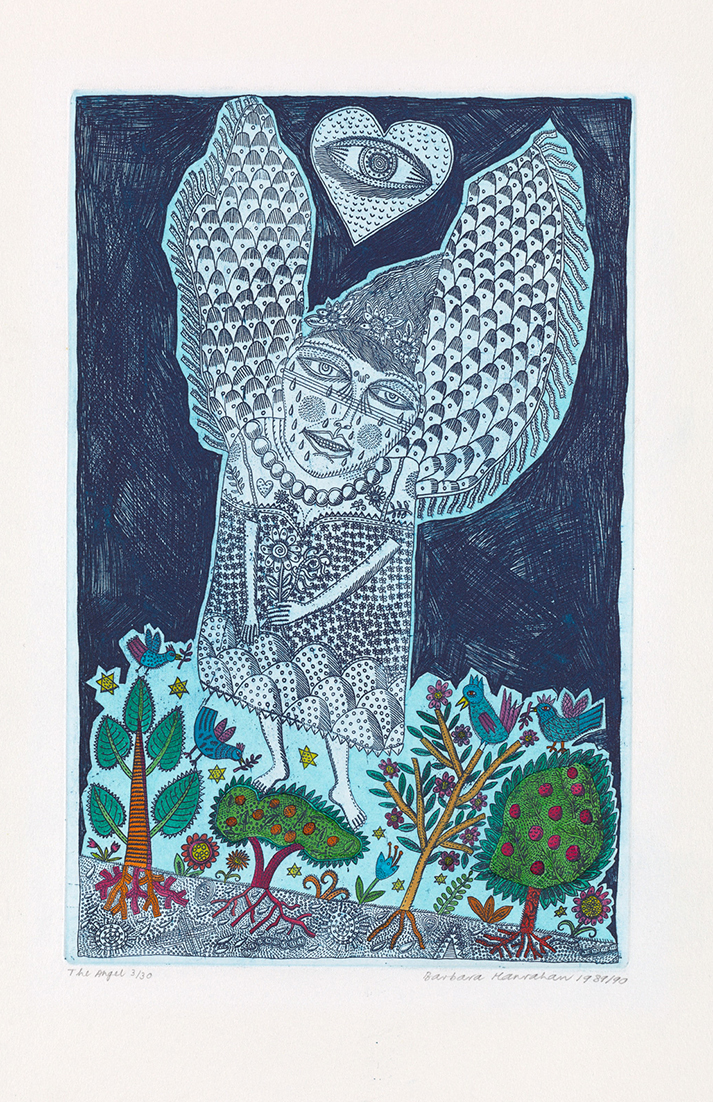

Barbara Hanrahan, The angel 1989-90, hand-coloured etching, colour inks on paper, 34.8 x 22 cm, Private collection, Adelaide, © the Estate of the artist, courtesy Susan Sideris 2020

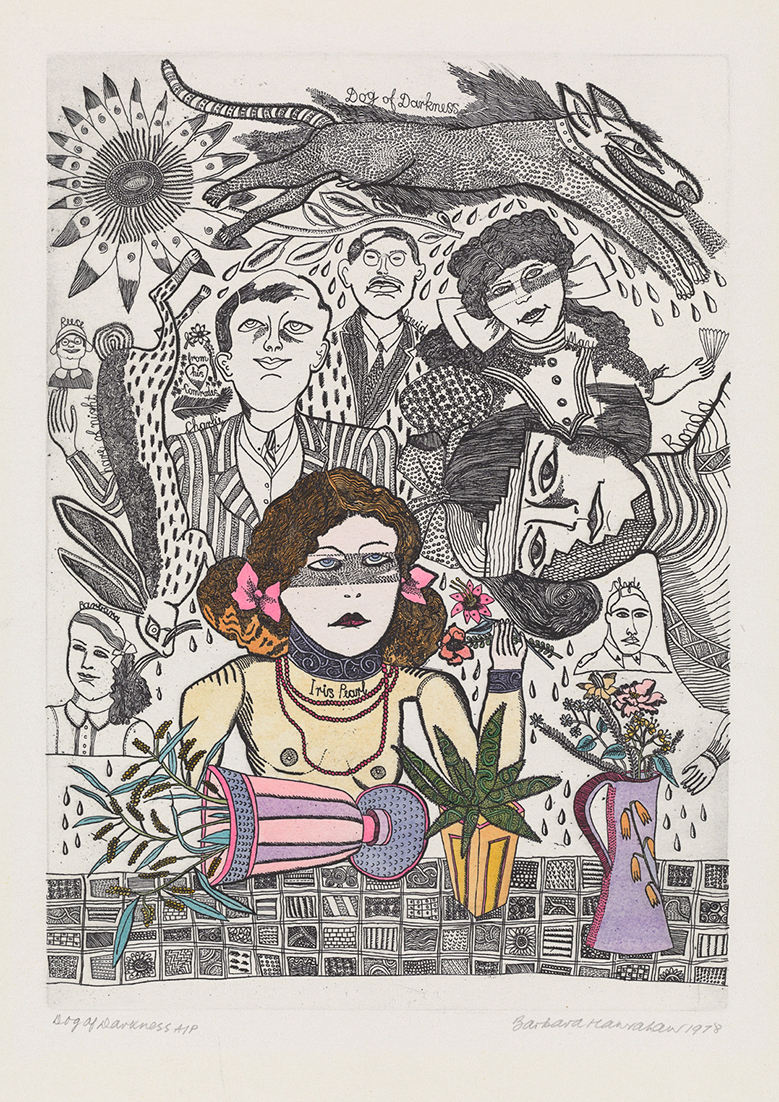

Barbara Hanrahan, Dog of darkness, 1978, hand-coloured etching with plate-tone, colour inks on paper, 35.5 x 25.3 cm, Private collection, Adelaide, © the Estate of the artist, courtesy Susan Sideris 2020

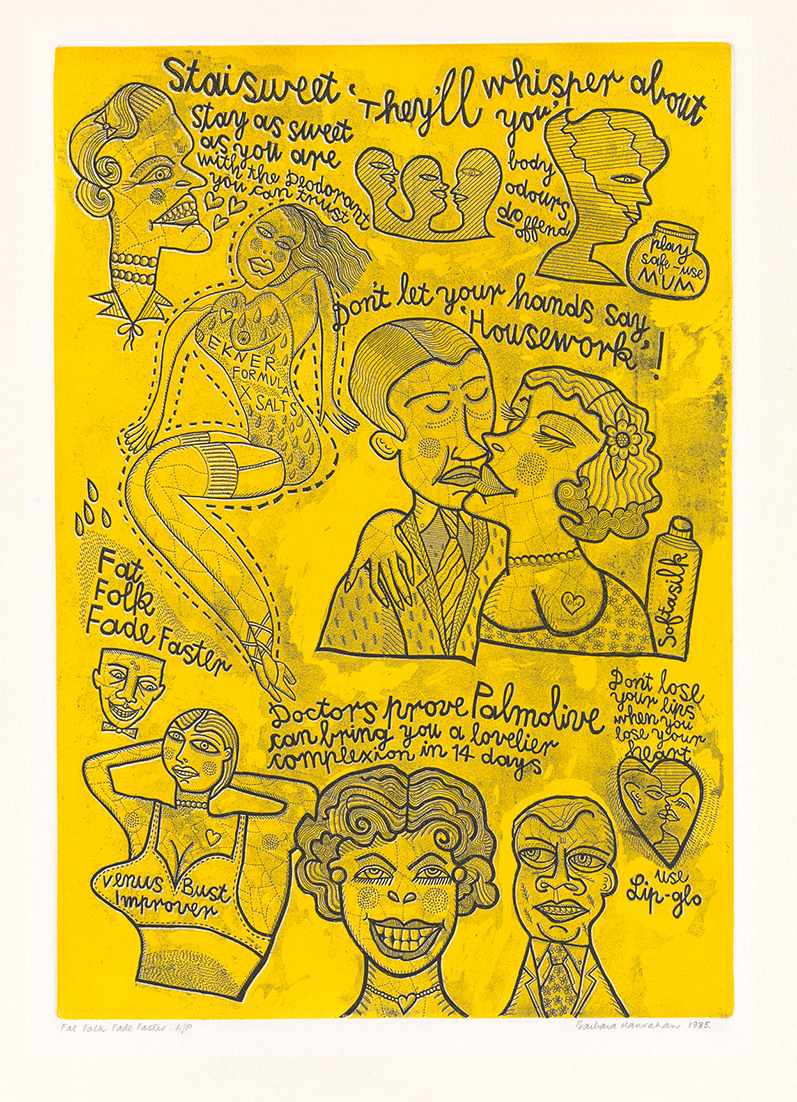

Barbara Hanrahan, Fat folk fade faster, 1985, etching, yellow and black ink on paper, 50.8 x 35.5 cm, Private collection, Adelaide, © the Estate of the artist, courtesy Susan Sideris 2020

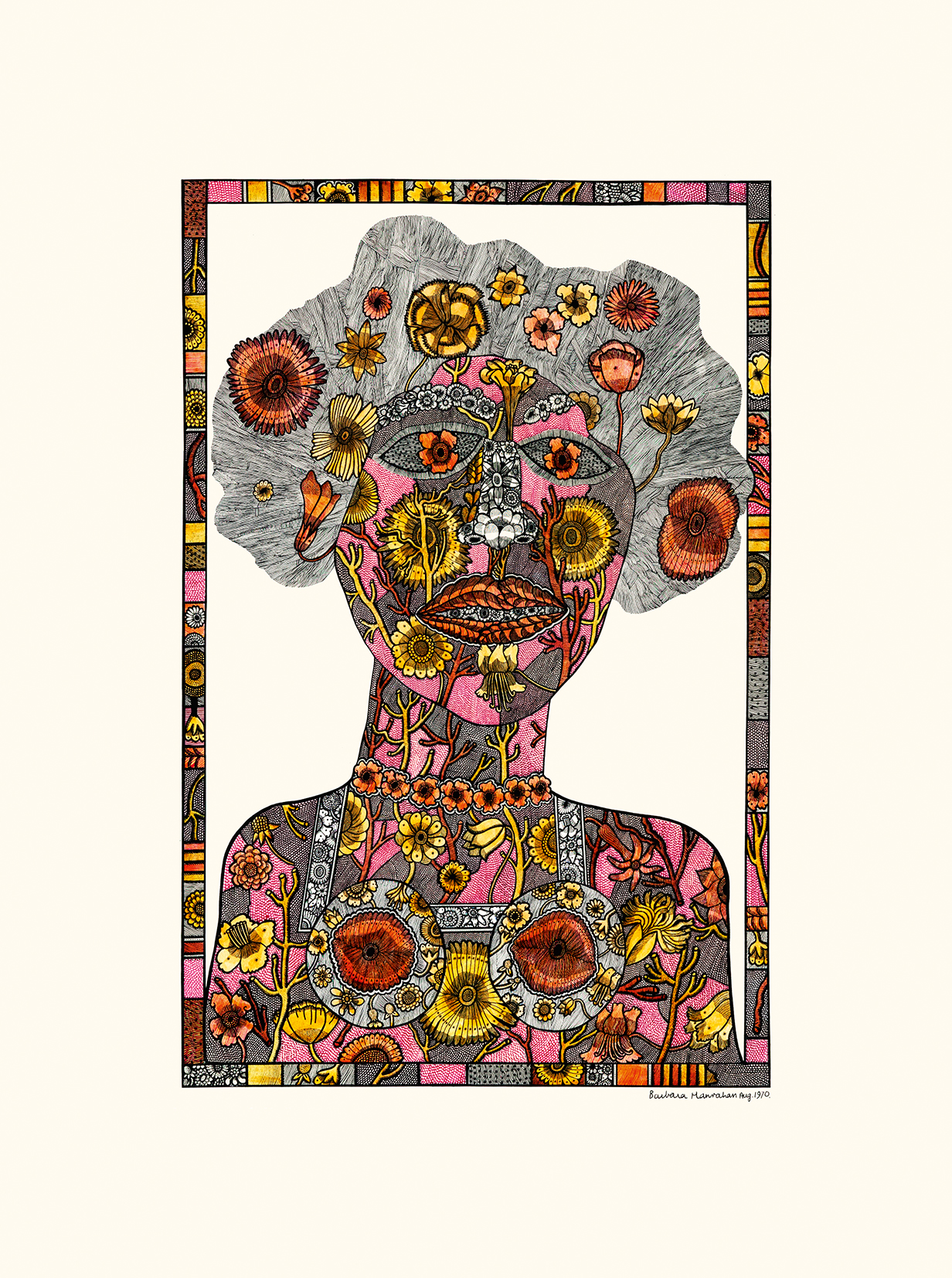

Barbara Hanrahan, Flora, 1970, pencil, gouache and clear varnish on board, 56.0 x 36.2 cm, Shirley Cameron Wilson Bequest Fund 2007, Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide 20072D5, © the Estate of the artist, courtesy Susan Sideris 2020

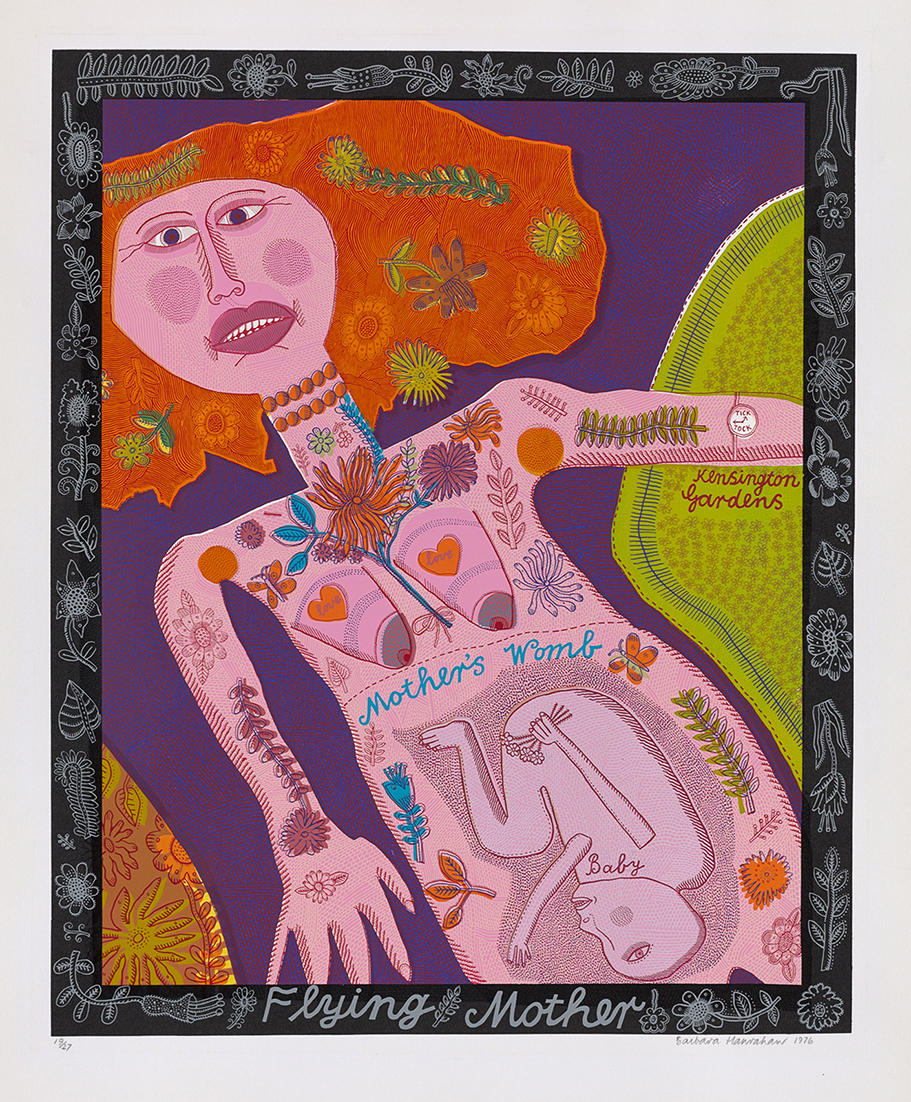

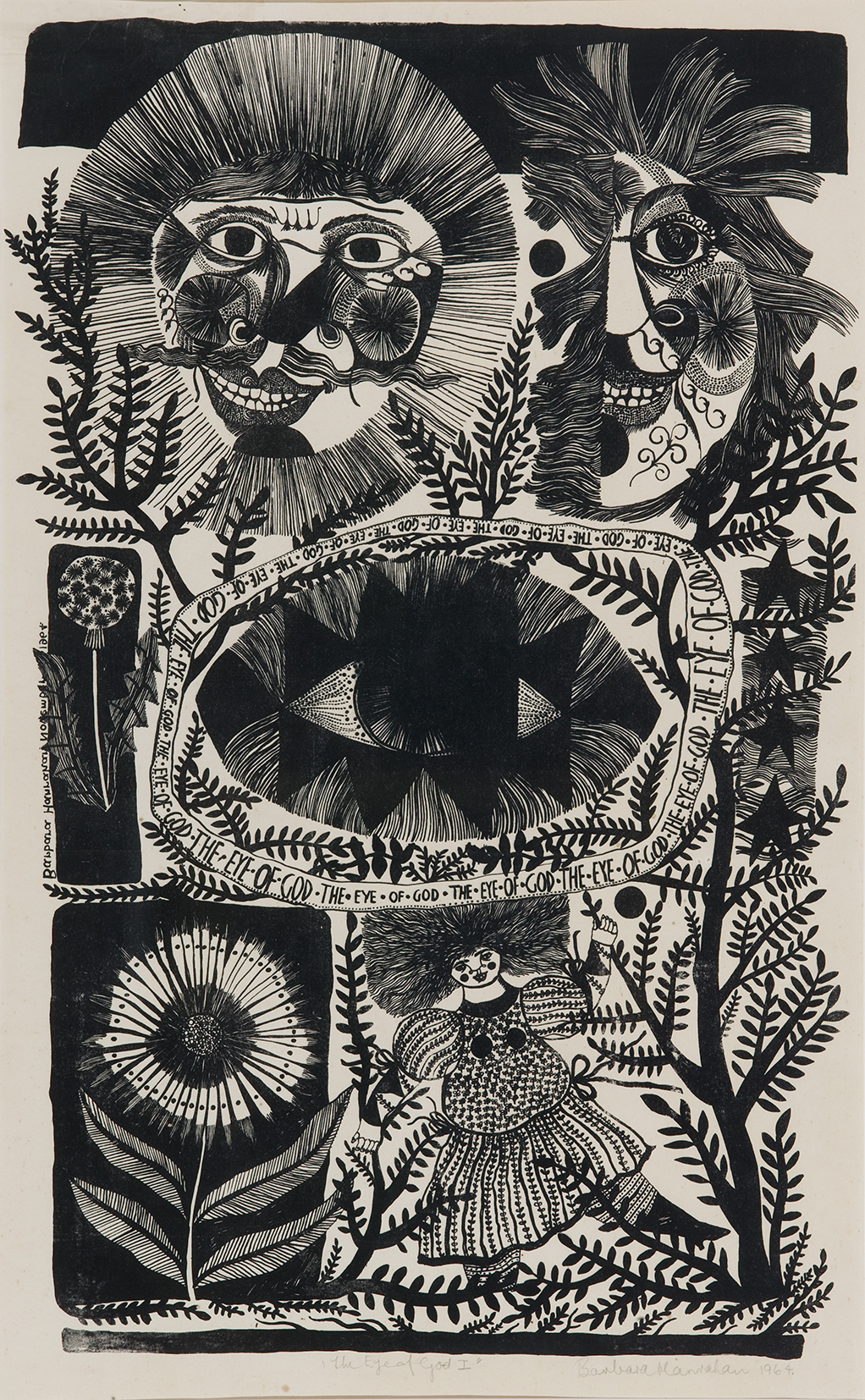

Barbara Hanrahan, The eye of God I, 1964, lithograph, ink on paper, 76.5 x 48.0 cm, Gift of Jo Steele 1996, Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide 962G13, © the Estate of the artist, courtesy Susan Sideris 2020

Q: What were some of the foundation ideas for this exhibition project?

A: Bee-stung Lips: Barbara Hanrahan works on paper 1960-1991 is the first major survey exhibition of Barbara Hanrahan’s prolific 30-year printmaking career that was set in motion in 1960 and ended with her untimely death at the age of 52.

Thirty years since the artist’s life was tragically cut short, we wanted this exhibition and accompanying catalogue to pay tribute to Hanrahan’s uncompromising and prolific practice as a visual artist. Given the ongoing relevance of her subject matter that challenges social expectations, particularly around the roles of women in society, we also wanted to introduce her work to a new generation of young people and contribute to broader discourse that is acknowledging the distinct and important voices of female artists in the Australian cultural landscape.

Q: How did the artwork selection take place?

A: The exhibition is curated by Flinders University Museum of Art (FUMA) Collections Curator Nic Brown. Given the imposts of COVID-19 during the development phase of the project, she focussed on collections accessible in Adelaide including at the Art Gallery of South Australia and the private collections of Hanrahan’s partner Jo Steele and gallerist Susan Sideris, as well as FUMA’s own holdings that comprise 23 works. As part of this process Brown sighted close to 400 works.

The selection includes some of the artist’s first works made in the 1960s and spans three decades ending with her final print made in 1991. Rather than presenting these chronologically however Brown distilled her selection according to four overarching themes which emerged from her research: sex, beauty and the stage; domestic comforts and anxieties; becoming plant, becoming animal; and celestial bodies and the afterlife.

Q: How does the exhibition manifest – what do visitors experience?

A: The exhibition comprises 186 works including woodcuts, linocuts, screenprints, lithographs, etchings and drypoints, as well as rarely-seen drawings, paintings, and collage. These range in scale from miniatures to larger format prints that are up to 80cm in height and vary from black and white to saturated multi coloured works – evincing the artist’s mastery of technique and illuminating Hanrahan’s signature decorative style.

Works are grouped according to the curatorial themes and presented by way of ‘salon hang’ underscoring the artist’s fertile vision of the world and indefatigable commitment to her craft.

Interpretive text is kept at a minimum in the space with artwork labels and interpretive material accessible via QR code. A short talk by the curator is presented in video format and is available to visitors as they enter the gallery. A longer video with Hanrahan’s partner – and collaborating printer – Jo Steele is available online together with a virtual tour of the show.

The exhibition catalogue, supported by the Gordon Darling Foundation, includes essays by Nic Brown, Jacqueline Millner (Associate Professor Visual Arts, La Trobe University) and Elspeth Pitt (Curator, Australian Art, National Gallery of Australia).

Q: What are some of the key works and what subject matter do they deal with?

A: Excerpts from Nic Brown’s catalogue essay Time Travel, Bees and Celestial Bodies in the Art of Barbara Hanrhan:

Informed by 1960s and 1970s British and American popular culture while living predominately in London between 1964 and 1978, Hanrahan produced a body of work that speaks to sexual politics, beauty ideals and performance in connection to consumer, media and popular culture, themes which continued throughout her career.

Hanrahan’s etchings Rock me mama (1983) and Homage to Buddy Holly (1966) depict hero and sex symbol imagery of the mid to late 1950s American male rock ‘n’ roll star – on stage and idolised by female groupies, most in various states of undress. While Buddy Holly pays homage to the boy-next-door singer’s quick rise and unfortunate demise, Rock me mama highlights the glitz and hype of Elvis Presley’s fame evidenced by ‘makin’ it with girls’, his bedazzled fans or his lover, the burlesque performer and movie star Tempest Storm, ‘everywhere I went’. [page 2]

Social expectations for women around the marriage institution as well as the cycles of family generations are suggested in Iris Pearl dreams of a wedding (1977). This screenprint features a private interior world with Hanrahan’s grandmother rendered as a young woman reclining in the manner of Titian’s (1488/90-1576) Venus of Urbino (1538) – the mythological goddess of love – on a decorative green chaise longue. Clothed in a strappy dress, coloured earth and seeming to sprout a garden fecund with flowers, one bare breast is revealed, echoing the Renaissance symbol of the maternal and erotic, and parodying the conservative wedding apparel ethereally outlined above. [page 4]

This entanglement between people and the natural world comes to the fore in Hanrahan’s Woman tree (1989), where a multi-trunked tree takes on human characteristics, revealing three female forms with clearly defined faces, breasts and montes pubis, and arms that reach toward the sun or wave a greeting. Their skin bears patches of textured bark while toes, buried beneath the earth, transform into roots and actively draw sustenance from the soil. The branch-arms sprout leaves and fingers grow pink ripening fruit which share a likeness to that of the laurel tree, calling to mind the plight of Daphne, the naiad-nymph in Greek mythology who metamorphosed into a laurel tree in her escape from the love of Apollo. [page 7]

From the late 1980s (with the resurgence of her cancer) through to her final work made before her death in 1991, Hanrahan regularly depicted angel subjects as another means to explore the eternal afterlife. In The angel (1989-90) a winged figure set against a cool, blackened universe foregrounds the composition and is watched over by ‘the feeling of…God’[A], Hanrahan’s eye of God iconography encased in a heart of love. She hovers, tiptoe, on a tree in a night-time forest lit by golden stars. Birds fly with twigs, seemingly to prepare nests for the next generation which speaks of spring and regeneration. At the same time this imagery evokes the symbol of the dove of peace that carries an olive branch. [page 8]

Q: What is it about printmaking that you most appreciate?

A: Elspeth Pitt makes the following observations about Hanrahan’s relationship to the printmaking process in her catalogue essay Print, Poetry and the Romantic Imagination: Barbara Hanrahan and William Blake

It is fascinating to consider how an artist comes to their medium, how it connects to or enhances the meaning of their work. For Blake, the methods of printmaking were entwined with spiritual exploration. He claimed the process by which he printed his illuminated books and prophetic texts was imparted to him by his deceased brother in a vision.[1] In The marriage of heaven and hell (c1790) he likened the caustic process of intaglio printing to an act of cleansing that allowed enhanced perception, writing that: ‘ … first the notion that man has a body distinct from his soul, is to be expunged; this I shall do by printing in the infernal method, by corrosives … melting apparent surfaces away and displaying the infinite which was hid. If the doors of perception were cleansed everything would appear to man as it is, in-finite.’[2]

Blake’s words would later be echoed by Hanrahan who said: ‘When I began making prints … I felt I had sloughed the false ‘me’ away and was in touch with the deepest part of my being which, in turn, was in touch with something so much greater than itself.’[3] Like Blake, the caustic process of intaglio, and by extension, the cutting of blocks, revealed to her a truer self within the broader context of an evolving, personal religion. In her diaries, too, she would situate printmaking in sacred terms, describing the print workshop at the South Australian School of Art as her ‘spiritual home’, and an ‘ecstasy in my life’.[4] She wrote: ‘Printmaking … saved me – it was a retreat to focus all the poetry and spirituality inside me … My God was there … The techniques of the print room. Etching and lithography, woodcuts, linocuts. The beautiful traditions, hand-done.’[5] Later, she would go further, referring to the material aspects of the print as sentient: ‘[I] Love the breathing porous paper’; of lithography: ‘The creamy limestone surface was so sensitive, it seemed a living thing’; and of her final linocuts: ‘I hold my breath as I cut each one … there comes a stage in the cutting … when the image comes alive and the figures I am cutting become the people I love.’[6] [7] [8]

[pp 23 & 24]

—

Bee-stung lips: Barbara Hanrahan works on paper 1960-1991 is on display at the Flinders University Museum of Art, Bedford Park until Friday 1 October, touring South Australian regional centres with Country Arts SA through 2022-2023 before travelling interstate. www.flinders.edu.au/museum-of-art/exhibitions

[A] Interview by the author with Jo Steele, 17 February 2021.

[1] Blake, p. 9.

[2] ibid., p 120.

[3] Mott, p. 44.

[4] Hanrahan, The diaries of Barbara Hanrahan, p. 63.

[5] ibid., p 323.

[6] ibid., p 183.

[7] Hanrahan, Kewpie doll, p. 132.

[8] Hanrahan, The diaries of Barbara Hanrahan, p. 301.

—

Join the PCA and become a member. You’ll get the fine-art quarterly print magazine Imprint, free promotion of your exhibitions, discounts on art materials and a range of other exclusive benefits.